Laura Elizabeth James

Laura Elizabeth James,1880-1969 was a much decorated New Zealand nurse. She was born on 12/12/1880 in Hokitika, New Zealand, a South Island mining town, the only child of Dr David Philip James (1848-1916) and Jane McLean Clayton (?-1940), who had married in 1875 and who divorced in 1883.1

We are indebted to John W Hawkins for sharing his research.

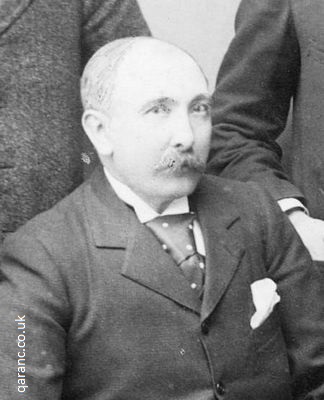

Laura's father, a respected Welshborn, London-trained doctor, went back to England in 1884 and did not return to New Zealand until 1892 (see Appendix). It is not clear who was primarily responsible for Laura's upbringing, but she was educated at Mrs Croasdaile Bowen's Private School, Christchurch and the Girls' College, Wellington. Her nursing training did not begin until she was 26, when between 1906 and 1909 Laura trained as a nurse under the long-serving Matron of Wellington Hospital, Miss Francis Keith Payne, reaching the position of Sister.

In January 1910 she sailed for Genoa via Sydney as a companion to the forty year old Miss Gertrude Ellen Meinertzhagen of Waimarama (travelling under the assumed name of Mrs G.E. Murray), who was pregnant with her first child. They spent some time in Italy and then proceeded to Montreux for Gertrude's confinement, although Laura left before this and continued on to London:2 Miss Laura James, who left Wellington early in December last, and joined the Friedrich der Grosse at Sydney on December 28, landed at Genoa on February 3, and has since visited the Riviera, Milan, Lake Maygiore, Montreux and Lausanne.

She arrived in London towards the end of April, and stayed here about ten days. At present Miss James is visiting relatives in South Wales, but will be going to Bristol and Bath, and back to London in July. Further than that she has made no plans as yet. Miss James was a Sister in Wellington Hospital, but resigned in November last, and has come to England with a view to entering if possible the Queen Alexandra Imperial Military Nursing Service. Her application to join the Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS) was successful and she enrolled on 03/11/1910 as a Staff Nurse, one of the few women from outside Britain who were in the QAIMNS before the outbreak of WW1. Her reference from the Matron of Wellington Hospital was favourable, but also noted: 'Slightly difficult to work with, but can be guided by good influence'.3 Her initial service was in Aldershot, London and Tidworth, Wiltshire. In August 1914, after Britain declared war on Germany, she was mobilised as a Sister and sent to France.

One of her letters home, written at No.10 General Hospital, Rouen on 12/11/1914 was published in Kai Tiaki:4

We mobilised on August 17th, 1914, had a week in London, and then went on to the Woolwich dockyards, picked up the troop train the same day, travelled down to Southampton and crossed that night to le Havre. Of course we had no idea where we were going until we were actually anchored outside le Havre the next morning. We waited four hours and then left at noon for Rouen.

It was a glorious day and the journey up the Seine was delightful. We formed a little procession going up the river. The British Hospital Ship St Andrew headed it with our transport next, then the hospital ship St Patrick, and finally the troopship with the R.A.M.C. officers, orderlies and the whole of the medical supplies and hospital equipment. We met with a tremendous reception all along the banks of the Seine. One heard nothing but 'Vive l'Angleterre', 'Vive la France', everywhere and flags were waved, and at every village the flags of different consulates were dipped in our honour. It was a great experience - one that I shall never forget. We reached beautiful old Rouen at 5 p.m. and then began the business of disembarking. We were billeted in private houses for two days and afterwards in a convent. Rouen was intended to be a big hospital base, and there were four other hospitals there. One was in working order and the others were nearly complete when the Germans began to advance on Amiens. No. 7 General Hospital had to retreat hurriedly to Rouen from Amiens. The Sisters had not even time to change their caps and aprons. They and their patients travelled in cattle trucks and had a terrible time of it. After they had been in Rouen a few days the order suddenly came through for the whole of the hospitals to pack up. By 5 o'clock the next evening we were all six general hospitals, which meant in all over 250 sisters and staff nurses - waiting on the Gare d'Etal ready to depart. We sat on our luggage for five hours and then left at midnight. The R.A.M.C. and equipment in the meantime left by boat. We had an appalling two days in a noncorridor train. We washed when and where we could.

Our rations were bully beef and biscuits - not the familiar household biscuit, but a good old dog biscuit. These items were supplemented by rolls which we bought at railway buffets and fruit and tomatoes given to us by kindly French people on the way. We passed several hospital trains, both English and French, packed with sick and wounded. They lay on straw in trucks and those who we saw and spoke to said they had been for four or five days on the way to the hospital ship at St. Nazaire. We were also bound for that port, which we reached in the early morning. Later in the day we went to Poin-chez-les-Pins, where we waited impatiently for further orders. It was a delightful seaside spot, so we bathed a great deal. This was our sole amusement during that trying wait.

A few days' later detachments were sent from various hospitals for railway station duty and for transport duty for England. Eventually we all began to move on again. No. 4 General Hospital went to Versailles; No. 5 to Angers and we back to Rouen, as also did No. 8 General Hospital. We got to work straight away at our camp. It is on the Champs des Course, a delightful spot with gravel soil and surrounded by a belt of trees. It is quite compact and just about as comfortable as we can make it. We shall be under canvass for two months and if all goes well huts will be ready for us in the winter. The country is very low-lying and consequently damp and foggy, already we have felt the cold at nights. Some of us passed miserable nights until we found a remedy. Our camp beds, of course, had nothing in the way of mattresses upon them, so were very hard upon one's poor bones. However, after a diligent search in the shops at Rouen we unearthed some imitation eiderdown quilts in the shape of sleeping bags, which we put on the bed first and then make up the bed on top and finally bring the sides and ends to meet on top and tie them with a rug on top to hide defects. This arrangement makes a warm and cosy nest. It requires a little tact in getting into bed, so as not to pull the clothes out at the sides. One has to sit on the pillows and after a series of wriggles one eventually gets into position. We made our resting place into cubicles by means of a wonderful selection of sheets and curtains, and each boudoir measures two yards by three yards. When our canvass chairs, bottles, washstands, etc. are in position I assure you there is absolutely no room to move. The luggage sits in loose-boxes nearby.

Our hospital will accommodate 520 patients and including the matron we ought to have a staff of 43 sisters and staff nurses, but for various reasons we have lost twelve, so it makes the rest of us much more hard worked. Of course, there are nursing orderlies as well, 66 in number. The hospital is well equipped, even to sheets and while blankets. The latter turned up today, October 3rd, and we had a strenuous day changing all the brown blankets with which we were equipped at first. In the midst of all this turmoil we were suddenly called over to our own camp to remove our belongings. We began our camp life in store tents, but as these leaked last night they were hauled down today, and lined marquees put up in their places. They are much warmer, but very dark. By the same token we also had white blanket given out to us. We even had two cats - Siamese. They were presented to our Matron by the Mother Superior of the convent in which fourteen of us stayed when we came to Rouen the second time. We were there ten days and we were sorry to leave. I have never experienced such kindness as was shown us by the Reverend Mother and Sisters.

It was an enclosed order, the second monastery of the Order of the Visitation. The convent is very old and full of treasure. The Mother took us all over and showed us everything. We saw most beautiful lace and embroidery done by the nuns from time to time. Well, enough of our adventures. I must tell you a little about the work. Nearly all the patients here are suffering from wounds caused by shrapnel shells bursting over their trenches. I do not think there are half a dozen in the camp with bullet wounds (single): some of the wounds are awful. For instance in my section (I have a section comprising three marquees on the surgical side), I have a man with a compound comminuted fracture of the femur. He was shot at very close quarters, consequently the wound to begin with was full of powder and the femur badly split up. Fortunately it just escaped the knee joint. At first the medical officers thought he would lose the leg, but it is going on satisfactorily and they think in a year's time it will be sound again. I have a piece of bone - about four inches in length - which was removed. It shows the mark where the bullet struck.

We have many arms which have had to be opened and up and drained, but they are doing well. There have been many minor operations for extraction of bullets, pieces of shrapnel, etc. I saw a wound made by a German dum-dum. The wound made by the ingress of the bullet is small, but coming out it tore the tissues terribly. We also have several men who have been shot through the lungs, including a German who is at the present moment dying. I was told that at the military hospital at Versailles a great many are dying from tetanus and tonight I am told there is a man in our hospital showing symptoms of it.

Some of the wounds are beyond description and the men tell us appalling stories of things that have happened. Surely this ghastly war cannot last for long. It is dreadful to think that so many Royal Army Medical Corp officers and men are killed and missing; those attached to the cavalry and field ambulances. According to the accounts heard from men some of the regiments have been badly cut up. I expect you saw the account of the wonderful charge the 9th Lancers made. They come from Tidworth, where I was stationed when the war broke out. Since writing above we have had another batch of wounded in, amongst them a quartermastersergeant of the 9th Lancers, who was injured by fragments of a melanite shell. He was literally peppered with wounds from head to foot, none very serious. How he escaped death is a marvel. Some soldiers beside him were killed outright - one being blown to pieces. A melanite shell is quite a new thing. It weighs 90 pounds and instead of containing bullets it is filled with scrap iron, which inflicts very nasty wounds. The soldiers call these shells 'coal boxes'.

Most of the men now in the hospital have come from Braesire and Soissons, where so much fighting is taking place. They are all wonderfully bright and cheerful in spite of the hard times they have experienced. They are not kept in bed unless absolutely necessary, so they amuse themselves playing cards and other games.

Another letter dated 14/02/1917 written by Laura while serving with No. 37 Field Ambulance was also published in the Kai Tiaki:5

I have been much interested in the New Zealand nurses letters of their experiences published in Kai Tiaki. I wonder if it would interest you to know something of a special hospital attached to a field ambulance. I believe there are only two or three such hospitals, with a small staff of sisters, in existence. They are much nearer the firing line than the casualty clearing stations. The one of which I am in charge is for severe abdominals, chest wounds or head injuries only. I have a sister, a staff nurse and orderlies as staff. Unfortunately the field ambulances are constantly moving on, so that one has to begin afresh to train raw material at each change. Some have only stayed a fortnight. The little hospital is in a chateau, and has accommodation for fifty officers and Tommies.

Invariably the patients reach us in a very collapsed condition, and consequently we have many deaths, which is very depressing. I recently had ten New Zealanders, four of who, unfortunately, died within a few hours of admission. The theatre is small, but very complete, and most of the operating is done at night. The reason being, that, as a rule, the patients do not reach us until after dark. We have found the weather conditions very trying of late. There has been twenty degrees of frost. The country round has been snow-clad and frost-bound for weeks. To give you an idea of some difficulties, I will tell you that our ward linen has been frozen in the tubs at the laundry for a month, indeed, some for six weeks! Coal and paraffin have been very short also. Ice has been found inside the chateau in all the water receptacles and on some of the windows (inside) to the depth of half an inch. Some days it was almost impossible to do more work than was absolutely necessary. Yet, in spite of it, we are flourishing. The last two or three days it has been thawing, and the cold is much more bearable.

This little hospital is about eight miles from Arras, a very much shelled town. Some little time ago I had the good fortune to be taken to see it. I had to wear a shell helmet, and carry a gas helmet by way of precaution. This, I think. Is an experience which has fallen to the lot of very few sisters. I will try and give you a few of the impressions of the town. It is within a mile and a quarter of the German lines. Although it is in ruins, it still resembles a town - every street is clearly there, with the front walls of the houses and shops standing on either side. As we passed through the ancient gateway- where one's passes were examined by the British and French sentries - its stillness struck one as being uncanny. Except for the echoing of one's footsteps in the empty streets, the occasional whirr of an aeroplane and the rat-tat-tat of German machineguns and the frequent thunder of our own guns, there were no sounds to be heard. There are still many of the inhabitants living in the cellars of the ruined buildings, but I did not see more than half a dozen during my two hours' stay there. In several places I was shown where masonry had been struck and brought down by fragments of shell less than twelve hours before I walked through the town. The greatest ruin is in the chief squares, and amongst the once prominent and beautiful buildings of this beautiful old Spanish-built city. The Hotel de Ville is merely a vast stone heap. The Cathedral still has some walls standing, but the ruin is a mass of fallen masonry. The Raseum nearby is also in the same condition. The big railway station I did not see, as it was too dangerous a spot to go near. In the squares there still remain barricades and barbed-wire entanglements erected by the Germans in the early days of the war.

Everywhere one went one saw signs of smashed bedsteads, chairs, articles of clothing and pictures still hanging on remaining walls. The thing that struck one very forcibly was, in spite of ruin everywhere, the extraordinary cleanliness and air of order in the streets, due to the work of the British Tommy. I saw much else of interest, but, of course, cannot for obvious reasons write about anything more. The guns have been very busy all day and whilst I have been writing this the force of the explosions has shaken the chateau considerably. At night the sky is lit up by each flash, and when an explosion sounds more than usually near, it gives one a horrid little quaking feeling. I recently returned from leave to England, and on my way back I spent the night at No. 6 Stationary Hospital, where Sister Ethel Dement (of Wellington Hospital) is stationed. Unfortunately she was away on leave. I saw her at Rouen many months ago, when the Australian General Hospital first arrived there. She was billeted for a night at the General Hospital, to which at that time I was attached. I have seen several New Zealanders from time to time in different parts of France. You may perhaps be interested to hear that I was 'mentioned' in dispatches in January last!

Ethel Dement had earlier mentioned Laura in a letter she wrote to Kai Tiaki:6.

The first nurse I met in France was Sister Laura James, who was stationed at No. 10 General Hospital, B.E.F. We were of course delighted to meet, not having seen each other for five years. Laura was therefore occasionally much nearer the firing line than the Casualty Clearing Stations, which would never have been closer to the front line than about 10km.

On 29/03/1917 a diary entry by Dame Maud McCarthy, the Matron-in-Chief, British Expeditionary Force, records that Miss James, in charge at No. 45 Field Ambulance, had reported her unit was closing on the 29th or 30th. All the equipment was sent to the Arras underground medical facility, known as Thompson's Cave, but this was bombed only a few days later. On 5th April Laura joined No. 41 Casualty Clearing Station, one of two then situated to the west of Arras at Agnes-le-Duisans; the other was No. 19, to which Laura was posted on 4th May. Her Military Medal Citation reads:7

On the night of 3rd May 1917, when Arras was being heavily shelled, Sister Laura James showed great courage, and by her coolness and devotion to duty succeeded in allaying the fears of the patients under her charge. She refused to leave the ward, although the hospital had been hit several times, 3 men being killed and 14 wounded. She was only prevailed on to leave when all the patients had been safely evacuated. London Gazette, 18 July 1917.

There is, however, an issue with this. The large number of Military Medal awards meant that not all were gazetted with citations and where there were multiple awards to people involved in the same action the citations, if they were given at all, could be similar, or even identical. In fact another nurse, Ethelinda Maude, did receive the Military Medal with exactly the same citation. She, like Laura, arrived at 19 CCS on 4th May, but having been transferred from a unit other than 41 CCS. There are various possible explanations, including the incorrect date having been included on the citation. Laura remained with 19 CCS until 20th June, but Ethelinda had left by 19th May, the day after Laura was officially promoted to Sister. Over the next few weeks Laura moved from No. 8 Stationary Hospital at Wimereux to No. 4 Casualty Clearing Station, then at Lozinghem, and on to No. 10 Stationary Hospital at St. Omer.

In September 1917 she was posted to No. 15 Ambulance Train, with which she travelled to Italy to join the Italian Expeditionary Force. Her Italian service officially commenced on 18th November and in February 1918 she was transferred to No. 11 General Hospital, Genoa. By May 1918 she was at No. 51 General Hospital, also at Genoa, being appointed Acting Matron from August that year. She returned to England on sick leave in April 1919.

Following the war the Wellington Dominion newspaper wrote:8

There are many who will remember Miss Laura James, a Wellington girl, one of the nurses trained under Miss Payne at the Wellington Hospital and who, with many others, has done such splendid service during the war. Miss James was nursing in a London hospital when war was declared, and was at once sent out to France with a large batch of nurses. She has had some exciting experiences, working close up to the firing line and often in hospit als while they were being shelled. On one occasion, in France, she was sister in charge of the operating theatre at night while shells were actually flying around. The reward was the Military Medal. Later Miss James was sent on to Italy, and was there a Matron in charge of a large hospital. A few months ago she returned to England for a much needed rest, and is now at a hospital there. Miss James was one of the nurses to march the seven miles in the peace procession and all received a wonderful reception from the onlookers. She has earned six ribbons in this war and twice been mentioned in dispatches. The medals are: [A.] R.R.C., M.M., the 1914 Star, General Service War Medal, the Victory Medal and the Allies Medal [the French 1914-18 Inter-Allied Victory Medal]. This is a splendid record for a New Zealand girl and one that her countrywomen might well be proud of.

She was awarded the Royal Red Cross (2nd class) in June 1919, with which she was invested by King George V at Buckingham Palace on 20/02/1920.9 The 1920 Historical Roll relating to female Military Medals notes that she was also awarded five overseas service chevrons - 1 red and 4 blue - and that she was twice mentioned in Dispatches: by General Sir Douglas Haig's of 13/11/1916 and General Lord Cavan's of 26/10/1918.10 She was thus one of the most decorated nurses of WW1. Laura returned to England from Italy in April 1919 and spent the next three months on sick leave. On returning to service her next postings were at Colchester and Wool (Bovington Camp, Dorset). Her father had died after a short illness, aged 69, on 24/09/1916, when Laura was serving at the Front.11

On 14/07/1919, Laura James wrote to the QAIMNS Matron-in-Chief requesting permission to return to New Zealand on a troopship to settle her father's estate, with which she was experiencing considerable difficulty. Her request for a duty passage was turned down and these matters remained unresolved in 1921.12

In that year, in a letter of 09/03/1921, she requested a transfer from Bovington Camp, Dorset to the London District in anticipation of a visit to England by the New Zealand solicitor winding up her late father's estate and to be closer to '… my friend who is helping me with the settlement of my affairs, and who resides at Hailsham, Sussex.' One of the letters on her service file dated 09/07/1921 was written from Windmill Hill Place, following a period of sick leave, and this was also noted as her contact address while on sick leave in 1928, 1929 and 1930.

Laura was posted to Gibraltar in 1924 and to Malta the following year, returning to the UK in 1926. In a letter on her service file dated 16/01/1925 there is the following comment: … it is noted with regret that this lady's conduct should have merited an unfavourable report, especially as a similar report has been made on a previous occasion. I am directed to request that you will be good enough to cause this lady to be informed that her conduct has incurred the severe disapproval of the Matron-in-Chief, and that unless an improvement is noted in her next Confidential Report the question of her retention in the force will have to be considered by the Army Nursing Board.

Unfortunately none of the Confidential Reports remains on the file, so the conduct concerned remains a mystery. In any event her conduct must have been found satisfactory thereafter and between 1926 and 1931 she served in London, Aldershot and Netley, Hampshire (the Royal Victoria Military Hospital), as well as undertaking 'trooping duties'.

In December 1931 she embarked for service in India, being stationed first at Poona and later at Quetta (now Pakistan). She was appointed Matron on 23/10/1932, having scored 78.6% in her examination taken in 1928. Thereafter she was keen to effect an exchange with another Matron to return to the UK, but in May 1933 she was admitted to hospital suffering from influenza, pleurisy and complications. She returned to England on sick leave later that month, not recommencing her duties until December 1933 at Aldershot. In November 1933, when it was still intended that she should return to India, she wrote again to the Matron-in-Chief requesting an exchange that would allow her to remain in the UK 'as I am anxious for urgent private reasons to complete the remainder of my service in the QAIMNS at a Home Station'. The request was granted and she initially remained at Aldershot, transferring to Catterick, North Yorkshire in 1935. After serving more than twenty three years in the QAIMNS she retired on 11/12/1937, being allowed to retain her Queen Alexander's badge.

Laura evidently remained close to Gertrude Murray throughout her life and received a legacy of £50.00 under her will when she died on 01/08/1937. Following Laura's father's death, she stated that her next of kin was a cousin, Katherine Margaret Ann George of 'Brooklands', Pendine, Laugharne, Carmarthenshire (born 02/09/1898, the daughter of Thomas and Alice George; died 31/01/1939), with whom she stayed on a number of occasions while on leave. This is notwithstanding the fact that her mother did not die (in New Zealand) until 1940. In 1939 Laura was living in retirement at Cherry Tree Cottage, Copden Oak, Biddenden, Kent and in 1947 moved to Walden Cottage, Sempstead Lane, Ewhurst Green, Sussex, possibly using a bequest she had received the previous year to purchase the property. In an exchange of correspondence concerning her pension entitlement in 1947 she referred to 'having recently benefited from the death of a relative', her aunt Alice George, who had died on 12/02/1946 (her uncle, Thomas George, had died on 14/11/1919). Katherine had left a life interest in all of her property to her mother when she died, but on Alice's death this passed to Laura.

In another such exchange in 1955, it is clear that one of her investments was a 5% mortgage on Bwichyr'nos Farm, Goodwick, Pembrokeshire to T.S. Rees for £750.

She never married and died at The Mount Nursing Home, 6 The Mount, St Leonard's-on-Sea, Sussex, England on 23/02/1969, apparently with no close living relatives. Probate was granted at Lewes, Sussex on 06/05/1969, her estate being valued at £6,703. She appointed National Provincial Bank as her executor and the estate was divided between Hilda M. Jones and Honorine Oonagh Couldrey (née Blackley, 09/11/1904-07/01/1973).

Her wish was to be cremated, which was carried out at Hastings Crematorium on 27/02/1969; her ashes were scattered there in the Garden of Remembrance and sadly there is not even an entry in the Book of Remembrance to recall her passing.

Our grateful thanks to John W Hawkins for kindly sharing his research. His acknowledgements reads:

I am extremely grateful to Sue Baker Wilson, QSM for pointing me in the direction of several sources and for her general support. Cheryl Ward and Sue Light have also written on Laura James.

APPENDIX

David Philip James, MRCS (Eng), LRCP (Lond), FRCS (Eng), (1848-1916).

David James was born in Narberth, Carmarthenshire, Wales in Dec Qtr 1847, the son of John James, a farmer, and his wife Elizabeth; his younger brother, George, was born in Jun Qtr 1849 and he also had an older step-brother, Thomas George (born 1833; died 14/11/1919).

David died after a short illness at his home in Sydney Street, Wellington, New Zealand on 24/07/1916. He was educated at the Grammar Schools in Carmarthen and Haverfordwest, then studying medicine at St Bart's Hospital, London, where he became gold medallist in clinical medicine in 1871. He also studied at the Royal Ophthalmic Hospital. He gained his qualifications on the following dates: MRCS (Eng) 1871; LRCP (Lond) 1886; FRCS (Eng) 1887. He was first registered as a medical practitioner in New Zealand on 22/04/1873, initially settling in Reefton, and was a surgeon at the Reefton Hospital 1874-6. He practised in Hokitika from 1876 to 1884 and from 1878 to 1884 was Surgeon Superintendent at the Westland Hospital.

Following his affair with Emily Reid and separation from his wife, he returned to England in 1884 for three years, gaining positions as Clinical Assistant at the Royal London Ophthalmic Hospital, the Central London Throat and Ear Hospital, and the Hospital for Women, Soho Square. In 1888, he left England, and spent some time travelling in Queensland and elsewhere, before finally returning to NZ in 1892, settling in Wellington. He was Honorary Physician at Wellington Hospital from 1894 to 1896 and Honorary Surgeon at Wellington Hospital from 1896 to 1910. He also acted as the Port Health Officer, Wellington. He was an ex-president of the Wellington Kennel Club and also a member of the Wellington Boxing Association.

Other than a few small bequests, all of David James' estate passed to Laura under his will. However, the sole executor appointed by David, Richard William McVilly (c.1862-1949), admitted to having almost no knowledge of his affairs at the time of his death and only later discovered that he owned property in Western Australia as well as New Zealand and that his wife was still alive.

For this reason probate was not granted until 1918 and the final settlement of the estate clearly took several more years. Katherine Margaret Anne George was the daughter of David's step-brother, Thomas, and his wife, Alice, née Lewis (1867-1946). Thomas was a civil engineer who became County Bridge Surveyor for Carmarthenshire and was responsible for designing most of the bridges erected in the county in the later nineteenth-century. He married Alice, who had been one of his servants, at the late age of 63.

Chronology

12/12/1880 Born at Hokitika.

1883 Parents' divorce; later attends schools in Christchurch and Wellington.

1906-1909 Trained at Wellington Hospital, New Zealand.

28/12/1909 Leaves Sydney for Genoa with Gertrude Murray.

03/11/1910 Enlists QAIMNS as Staff Nurse; posted to Aldershot.

15/12/1912 London.

11/06/1914 Tidworth.

17/08/1914 Mobilised as Sister; BEF, France & Belgium No. 10 General Hospital, St. Nazaire and Rouen No. 6 Stationary Hospital.

01/08/1915 No. 10 General Hospital.

25/08/1915 No. 23 General Hospital.

21/10/1915 Abbeville.

02/1917 No. 37 Field Ambulance.

03/1917 No. 45 Field Ambulance.

05/04/1917 No. 41 Casualty Clearing Station.

04/05/1917 No. 19 Casualty Clearing Station.

18/05/1917 Officially promoted Sister.

20/06/1917 No. 8 Stationary Hospital, Wimereux.

10/07/1917 No. 4 Casualty Clearing Station No. 10 Stationary Hospital, St. Omer.

17/09/1917 No. 15 Ambulance Train (leaves for Italy 09/11/1917; arrives 11/11/1917).

16/11/1917 BEF, Italy (acting Matron 22/08/1918 to 22/04/1919).

24/02/1918 No. 11 General Hospital, Genoa.

22/05/1918 No. 51 Stationary Hospital, Genoa.

23/04/1919 Sick & sick leave 14/07/1919 Colchester (reverts to Sister).

21/04/1920 Wool, Bovington.

16/07/1921 London.

21/03/1924 Gibraltar.

19/03/1925 Malta.

10/09/1926 London (returns on sick leave).

30/11/1926 Aldershot (treated at Cambridge Hospital, Aldershot in 1928).

07/12/1928 Passed examination for Matron.

03/1929 On leave at 'Overseas', West Hill, St Leonard's-on-Sea, Sussex.

08/1929 On sick leave.

08/04/1930 London.

22/09/1930 Trooping duty.

13/11/1930 Netley.

21/11/1930 Trooping duty.

17/02/1931 Netley.

26/02/1931 Trooping duty.

17/04/1931 London.

21/12/1931 Embarked for India.

13/01/1932 BMH Poona permanent duty.

10/06/1932 18 days privilege leave.

28/06/1932 BMH Poona permanent duty.

23/10/1932 Appointed Matron.

07/01/1933 Quetta.

03/05/1933 Admitted to hospital.

12/05/1933 On sick list in hospital.

20/05/1933 Passed medical board.

27/05/1933 Embarked for UK sick leave.

04/12/1933 Aldershot.

08/01/1935 Catterick.

11/12/1937 Completes service.

1939 Living at Biddenden, Kent.

1947 Living at Ewhurst Green, Sussex.

23/02/1969 Dies at St Leonard's-on-Sea, Sussex

06/05/1969 Probate granted at Lewes, Sussex

References

1 [New Zealand] Daily Telegraph, 27/10/1883. The action for a judicial separation, initiated by Jane, was due to physical cruelty and the adultery of her husband with Emily Reid (née Manning), wife of Robert Caldwell Reid of Hokitika; it was withdrawn on the basis of a settlement being made on her of £1,100, with payment of costs.

2 [New Zealand] Evening Star, 15/06/1910.

3 Quoted by Sue Baker Wilson from WO25/3956 https://www.nzetc.co.nz/PDF/Arras%20letters.pdf [accessed 10/05/2016]. Her service record is at the National Archives: WO 399/4234.

4 Kai Tiaki: the Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand, vol. 8, no. 1, (January 1917), p. 33.

5 Kai Tiaki: the Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand, vol. 10, no. 3, (July 1917), p. 133.

6 Kai Tiaki: the Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand, vol. 9, no. 4, (October 1916), p. 14.

7 London Gazette, No. 30188, 18 July 1917, p. 7275.

8 [Wellington] Dominion, 27/09/1919.

9 London Gazette, No. 31380, 3 June 1919.

10 London Gazette, No. 29890, 4 January 1917, p. 250 and No. 31106, 6 January 1919, p. 286.

11 [New Zealand] Evening Post, 24/07/1916. There is a Wellington probate file dated 1918.

12 'A much-decorated nurse' in Kai Tiaki: the Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand, vol. 12, no. 4, (October 1919), p. 170.

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

My PTSD assistance dog, Lynne, and I have written a book about how she helps me with my military Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, anxiety, and depression. I talk about my time in the QAs and the coping strategies I now use to be in my best health.

Along the way, I have had help from various military charities, such as Help for Heroes and The Not Forgotten Association and royalties from this book will go to them and other charities like Bravehound, who paired me with my four-legged best friend.

I talk openly about the death of my son by suicide and the help I got from psychotherapy and counselling and grief charities like The Compassionate Friends.

The author, Damien Lewis, said of Lynne:

"A powerful account of what one dog means to one man on his road to recovery. Both heart-warming and life-affirming. Bravo Chris and Lynne. Bravo Bravehound."

Download.

Buy the Paperback.

This beautiful QARANC Poppy Pin Badge is available from the Royal British Legion Poppy Shop.

For those searching military records, for information on a former nurse of the QAIMNS, QARANC, Royal Red Cross, VAD and other nursing organisations or other military Corps and Regiments, please try Genes Reunited where you can search for ancestors from military records, census, birth, marriages and death certificates as well as over 673 million family trees. At GenesReunited it is free to build your family tree online and is one of the quickest and easiest ways to discover your family history and accessing army service records.

More Information.

Another genealogy website which gives you access to military records and allows you to build a family tree is Find My Past which has a free trial.

Former Royal Air Force Regiment Gunner Jason Harper witnesses a foreign jet fly over his Aberdeenshire home. It is spilling a strange yellow smoke. Minutes later, his wife, Pippa, telephones him, shouting that she needs him. They then get cut off. He sets straight out, unprepared for the nightmare that unfolds during his journey. Everyone seems to want to kill him.

Along the way, he pairs up with fellow survivor Imogen. But she enjoys killing the living dead far too much. Will she kill Jason in her blood thirst? Or will she hinder his journey through this zombie filled dystopian landscape to find his pregnant wife?

The Fence is the first in this series of post-apocalyptic military survival thrillers from the torturous mind of former British army nurse, now horror and science fiction novel writer, C.G. Buswell.

Download Now.

Buy the Paperback.

If you would like to contribute to this page, suggest changes or inclusions to this website or would like to send me a photograph then please e-mail me.

Free Book.

The death of the Brotherhood will be avenged.

RAF gunner Jason Harper and a team of Special Air Service operators are enraged after the death of their brothers by a terrorist drone strike. They fly into south-eastern Yemen on a Black-op mission to gather intelligence and avenge the death of their comrades.

Can they infiltrate the Al-Queda insurgents' camp, stay undetected, and call down their own drone missile strike and get home safely?

Will they all survive to fight another day?

Operation Wrath is a free, fast-paced adventure prequel to the non-stop action The Fence series by military veteran author C.G. Buswell.

Download for free on any device and read today.

This website is not affiliated or endorsed by The Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps (QARANC) or the Ministry of Defence.