» Site Map

» Home Page

Historical Info

» Find Friends - Search Old Service and Genealogy Records

» History

» QAIMNS for India

» QAIMNS First World War

» Territorial Force Nursing Service TFNS

» WW1 Soldiers Medical Records

» Field Ambulance No.4

» The Battle of Arras 1917

» The German Advance

» Warlencourt Casualty Clearing Station World War One

» NO 32 CCS Brandhoek - The Battle of Passchendaele

» Chain of Evacuation of Wounded Soldiers

» Allied Advance - Hundred Days Offensive

» Life After War

» Auxiliary Hospitals

» War Graves Nurses

» Book of Remembrance

» Example of Mentioned in Despatches Letter

» Love Stories

» Autograph Book World War One

» World War 1 Letters

» Service Scrapbooks

» QA World War Two

» Africa Second World War

» War Diaries of Sisters

» D Day Normandy Landings

» Belsen Concentration Camp

» Italian Sailor POW Camps India World War Two

» VE Day

» Voluntary Aid Detachment

» National Service

» Korean War

» Gulf War

» Op Telic

» Op Gritrock

» Royal Red Cross Decoration

» Colonels In Chief

» Chief Nursing Officer Army

» Director Army Nursing Services (DANS)

» Colonel Commandant

» Matrons In Chief (QAIMNS)

Follow us on Twitter:

» Grey and Scarlet Corps March

» Order of Precedence

» Motto

» QA Memorial National Arboretum

» NMA Heroes Square Paving Stone

» NMA Nursing Memorial

» Memorial Window

» Stained Glass Window

» Army Medical Services Monument

» Recruitment Posters

» QA Association

» Standard

» QA and AMS Prayer and Hymn

» Books

» Museums

Former Army Hospitals

UK

» Army Chest Unit

» Cowglen Glasgow

» CMH Aldershot

» Colchester

» Craiglockhart

» DKMH Catterick

» Duke of Connaught Unit Northern Ireland

» Endell Street

» First Eastern General Hospital Trinity College Cambridge

» Ghosts

» Hospital Ghosts

» Haslar

» King George Military Hospital Stamford Street London

» QA Centre

» QAMH Millbank

» QEMH Woolwich

» Medical Reception Station Brunei and MRS Kuching Borneo Malaysia

» Military Maternity Hospital Woolwich

» Musgrave Park Belfast

» Netley

» Royal Chelsea Hospital

» Royal Herbert

» Royal Brighton Pavilion Indian Hospital

» School of Physiotherapy

» Station Hospital Ranikhet

» Station Hospital Suez

» Tidworth

» Ghost Hunt at Tidworth Garrison Barracks

» Wheatley

France

» Ambulance Trains

» Hospital Barges

» Ambulance Flotilla

» Hospital Ships

Germany

» Berlin

» Hamburg

» Hannover

» Hostert

» Iserlohn

» Munster

» Rinteln

» Wuppertal

Cyprus

» TPMH RAF Akrotiri

» Dhekelia

» Nicosia

Egypt

» Alexandria

China

» Shanghai

Hong Kong

» Bowen Road

» Mount Kellett

» Wylie Road Kings Park

Malaya

» Kamunting

» Kinrara

» Kluang

» Penang

» Singapore

» Tanglin

» Terendak

Overseas Old British Military Hospitals

» Belize

» Falklands

» Gibraltar

» Kaduna

» Klagenfurt

» BMH Malta

» Nairobi

» Nepal

Middle East

» Benghazi

» Tripoli

Field Hospitals

» Camp Bastion Field Hospital and Medical Treatment Facility MTF Helmand Territory Southern Afghanistan

» TA Field Hospitals and Field Ambulances

Queen Alexandra's Military Nursing Service for India

Information and history of the QAMNSI and the British Military Hospitals in India

From 1858 to 1947 part of the British Empire was India where British troops acted as a security force from 1903 to 1947 with the Indian Army. Their role was primarily to defeat against attacks by Russian troops from Afghanistan. The Indian Army saw active service in World War I and WWII. The British element of the Indian Army was withdraw in 1947, two years after the end of the Second World War.

The book Sub Cruce Candida: A Celebration of One Hundred Years of Army Nursing

They were known as QAMNSI (Queen Alexandra's Military Nursing Service for India) until this service was amalgamated in 1926 with the QAIMNS. Though existing members were allowed to continue on their previous terms of service until retirement. Thus a few of the QAMNSI can be found in the Indian Army List up to the Second World War.

In the Company of Nurses: The History of the British Army Nursing Service in the Great War

This time of colonial ruling was known as the British Raj which was Hindi for rule. India was known as The Jewel In The Crown. Many people may remember the 1984 TV series of the same name which starred Charles Dance, Peggy Ashcroft, Art Malik, Tim Piggot-Smith, Saeed Jaffrey and Judy Parfitt. It featured several QAs and Indian hospitals but I'm not sure who the actresses were that played the nursing sisters.

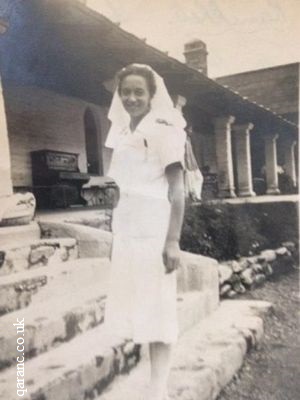

In the photo above is Sister Price in QA uniform in India, taking tea on a veranda. Read more about her service career during the Second World War on the War Diaries Nursing Sisters page.

As the British ruling in India continued the India Office paid more attention to the medical and nursing needs of soldiers. Miss Ada Hind who had experience as a Sister in Charge at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Suez, Egypt was asked to form the Indian Army Nursing Service but declined because of her own ill health. Instead two nursing sisters Miss Loch and Miss Oxley were chosen by the India Office to supervise and train nurses in the military hospitals in India and to work with the men of the Army Hospital Corps (cited in the book Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps (Famous Regts. S)

Miss Loch and Miss Oxley became Nursing Superintendents, or more correctly their title being Lady Superintendent, and took eight nursing sisters from Britain to India in 1888 to form the Indian Army Nursing Service (IANS).

In the same year Miss loch and four of the sisters saw field service at the Black mountain Expedition in North West India (cited in the book Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps (Famous Regts. S)

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

My PTSD assistance dog, Lynne, and I have written a book about how she helps me with my military Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, anxiety, and depression. I talk about my time in the QAs and the coping strategies I now use to be in my best health.

Along the way, I have had help from various military charities, such as Help for Heroes and The Not Forgotten Association and royalties from this book will go to them and other charities like Bravehound, who paired me with my four-legged best friend.

I talk openly about the death of my son by suicide and the help I got from psychotherapy and counselling and grief charities like The Compassionate Friends.

The author, Damien Lewis, said of Lynne:

"A powerful account of what one dog means to one man on his road to recovery. Both heart-warming and life-affirming. Bravo Chris and Lynne. Bravo Bravehound."

Download.

Buy the Paperback.

This beautiful QARANC Poppy Pin Badge is available from the Royal British Legion Poppy Shop.

For those searching military records, for information on a former nurse of the QAIMNS, QARANC, Royal Red Cross, VAD and other nursing organisations or other military Corps and Regiments, please try Genes Reunited where you can search for ancestors from military records, census, birth, marriages and death certificates as well as over 673 million family trees. At GenesReunited it is free to build your family tree online and is one of the quickest and easiest ways to discover your family history and accessing army service records.

More Information.

Another genealogy website which gives you access to military records and allows you to build a family tree is Find My Past which has a free trial.

Miss Loch later became the Senior Lady Superintendent of the Queen Alexandra's Military Nursing Service for India (QAMNSI).

The title of Lady Superintendent was replaced when the QAMNS (India) were amalgamated to the QAIMNS in 1926. Instead the title became Principal Matron and then Chief Principal Matron.

During these British Raj years the medical needs of the British Army and their families were then met by the QAMNS (Queen Alexandra's Military Nursing Service) for India (known as the QAIMN[I]) until they were amalgamated to the QAIMNS in 1926 by the War Office.

The QAIMNS (Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service) with the RAMC (Royal Army Medical Corps) continued to care for British servicemen and women and their families. The Indian servicemen were cared for in Indian Military Hospitals which were staffed by Indian doctors, orderlies and members of the Indian Military Nursing Service (IMNS). Conditions were much different under this culture and hygiene standards were much lower than what any QA's would have approved.

By 1929 there were 199 QAIMNS nurses serving in India and this increased to 288 QAs by 1935 (cited in the book Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps (Famous Regts. S)

British Military Hospitals in India included the Delhi Military Hospital, Station Hospital Rhanikhet India, Station Hospital Bareilly, Mody Khana Military Hospital, Military Hospital Kasauli and the British Military Hospital Ambala the Punjab.

The QAs were treated well in India and enjoyed a good social life and social status.

We'd like some help with identifying the group of nurses in this photo. They don't seem to be wearing the QA medal, but do have ribbons and scarlet bands on their wrists which may indicate Nursing Sister rank. The nurses wearing tropical uniform was taken by a Bombay/Mumbai photographer, perhaps in the inter war years. We are not sure if they are members of the Queen Alexandra's Military Nursing Service for India.

Members of the QAMNSI had the same medal as the regular QAs. For example, pictured below is the cape badge which belonged to Sister E M Maclean ARRC QAMNSI.

Former Royal Air Force Regiment Gunner Jason Harper witnesses a foreign jet fly over his Aberdeenshire home. It is spilling a strange yellow smoke. Minutes later, his wife, Pippa, telephones him, shouting that she needs him. They then get cut off. He sets straight out, unprepared for the nightmare that unfolds during his journey. Everyone seems to want to kill him.

Along the way, he pairs up with fellow survivor Imogen. But she enjoys killing the living dead far too much. Will she kill Jason in her blood thirst? Or will she hinder his journey through this zombie filled dystopian landscape to find his pregnant wife?

The Fence is the first in this series of post-apocalyptic military survival thrillers from the torturous mind of former British army nurse, now horror and science fiction novel writer, C.G. Buswell.

Download Now.

Buy the Paperback.

If you would like to contribute to this page, suggest changes or inclusions to this website or would like to send me a photograph then please e-mail me.

Lt Col Edna Burrows

Edna Burrows (nee Padua) had three sisters and two brothers. Her father was able to get work in the Kolar Goldfields, so the family settled there in the early part of

the last century.

Edna Burrows (nee Padua) had three sisters and two brothers. Her father was able to get work in the Kolar Goldfields, so the family settled there in the early part of

the last century.

Edna together with two sisters, Adelaide and Daisy, wanted to be nurses and were trained at General Hospital , Madras. During her training Edna met Frank Burrows who was in the Madras Police Department and when she completed her nurses training they married and settled in St. Thomas Mount. They had two children, Gwen and Derrick, and lived very happily until tragedy struck in January 1940. It was a motor accident that happened on Mount Road, Madras. Frank had multiple injuries and died two days later. Edna was in hospital for eight months with injuries.

When she was discharged from hospital, she wasted no time and joined the Indian Military Nursing Service as a Private and rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, receiving the highest award in nursing from King George V1, the Royal Red Cross India Medal in his Birthday Honours for her work with PaiForce (Persia and Iraq Force). At that time there were only six nurses in the world to receive the RRC award. She served in I.M.H. (Indian Military Hospital) Jubbulpore where her work had been much appreciated and the RRC recognised her excellence in nursing.

After World War 1, Edna applied for several positions in nursing and finally accepted work as Principal Matron at the hospital in Andaman and Nicobar Islands and remained there until her retirement.

To be gentle, charitable and humane came naturally to Lt Col Edna Burrows. She spent the last years of her life in Whitefield, Bangalore, and passed away in 1971.

Originally published as (Burrows, D.,F. (2006) as written for Anglos in the wind. p.26.) and reproduced on Qaranc.co.uk with kind permission of Lt Col Edna Burrows Son Derrick and Grand-Daughter Georgina.

If you can help with any additional information about Lt Col Burrows, her colleagues or place of work then please contact Qaranc.co.uk

Read more about the RRC medal on the Royal Red Cross Medal page.

Surviving Tenko: The Story of Margot Turner

World War Two in India

This all changed with shortages of nurses and servicemen during World War Two. A QA sister was sent to work in an Indian Military Hospital for the first time in 1941. This was Sister Gwendoline Jones of the QAIMNS who was posted to the province of Gowali with an RAMC officer. They were to care for the wounded of the Gowali Regiment who were returning from North Africa. She soon found volunteers from the locals which included two trained nurses. This Indo British unit was so successful that QAs began to work in Indian General Hospitals with the Sisters of the Indian Military Nursing Service (IMNS). This saw the formation of the Combined British Indian General Hospital (CGH). There is more written about Sister Gwendoline and her work in setting up the hospital at Gowali 7000 feet up in the Himalayas in the book Quiet Heroines: Nurses of the Second World War

India was thrust into WWII when Japan invaded Burma. Casualties of war were taken to India for treatment and the first were men of the 17th British and Indian Division.

Sister Gwendoline Jones was sent to the tented 75th Indian General Hospital near the Brahmaputra River North East India as Assistant Matron. It was mostly staffed by Indian Military Nursing Services Sisters, though she was joined by several QAs and RAMC officers. Orderlies and nursing assistants were employed from the local population of the Bengal. Supplies were limited and supplied by the Indian Red Cross and Miss Jones and her staff had to improvise and make use of what little they had to cope with the many patients arriving by ambulance train.

Once these patients had their emergency treatment and operations they were evacuated to base hospitals by RASC drivers (Royal Army Service Corps) in ambulances.

Grey and Scarlet : letters from the war areas by army sisters on active service

Below are photos and memories of serving as a QA in India from "What Are The Wild Waves Saying?” by Sheila GB Jarvis (nee Cranch) who wrote these fascinating memoirs for her grandchildren and kindly allowed qaranc.co.uk to display her photos and extracts. Sheila was a Nursing Sister in the Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve for India. Sheila graduated after four years RN training at Western Infirmary from 1939 to 1943. In the photograph below Sheila Gerard Bentley Cranch can be found on the second row, second from right:

Sheila decided to join the army and tells her story:

It was not until I heard about the army that is the QAIMNS/R (Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve), that I brightened, because there was mention of overseas service, Belgium or Africa being two possibilities. The idea of travel did appeal, so I applied and was granted an interview, passed this, was accepted, and told to report back to them for my orders as soon as I had received my uniform.

In the meantime, I was to purchase a black tin trunk and to have my name, rank, serial number and QAIMNS/R painted on in large white letters on the lid. I learned later that tin survived the tropical rain, heat, humidity and dust far better than leather. Leather tended to go mouldy, and all one's clothes smelled awful. This I found out by adding a small leather suitcase to my gear. The tailor came down from Harrods to measure us for indoor and outdoor uniforms. I thought this exciting, and was delighted to wear the smart clothes he sent back to us.

The outdoor, off duty or travelling uniform consisted of a heavy grey melton wool greatcoat trimmed with brass buttons and red flashes on the collar and epaulettes with brass pips denoting our rank. It included a well-cut grey suit with brass buttons and red flashes on the collar, white blouses and matching grey peaked cap. There were dark grey cotton poplin uniform dresses for ward duty wear, shoulders covered by the original capelet worn by the QAIMNS/R since the days of Queen Alexandra.

The white cap, a traditional square of white starch muslin folded into a triangle, light and easy to wear, almost entirely covered the hair. The tropical whites included white button front drill uniform, worn with white stockings, white shoes and white caps for hot weather, and for off duty wear, a huge white topee. We were issued khaki drill jackets, trousers, skirt and blouses, also khaki wool trousers and a battle dress jacket, a matching cap. I loved the battle dress jacket, kept it, and brought it to Canada. Although the great coats are long gone, I still have the splendid gray cloak lined with scarlet from the QAIMNS/R.

I arrived in Oxford where we marshalled, awaiting posting, attending lectures and collecting more kit. I had a bedroll containing the bed, a sort of trellis which was set up and the roll placed on top. I could pack one or two books into the bedding roll, flashlight, even nightie or pyjamas. This meant that I could quickly set up once I had arrived somewhere. Also in the bedding roll there was a canvas washbasin, and a bath, both made from squares of green canvas with loops at the corners which dropped over their own trellises. You will not be too surprised, I'm sure, that I managed a small stove, tea kettle and mug as well as the standard army issue water bottle. We made tea everywhere, as you can imagine.

Of the voyage to India Sheila remembers:

Our group was directed towards the gangplanks. We went aboard, found our cabins, left our luggage, and returned immediately to the upper deck to hang over the rail and watch the action; and there was plenty of action. Troops were boarding, simultaneously huge cranes were swinging over and dropping cargo into the hold. The noise was deafening: grinding gears, screaming machinery, men shouting above the din. We stood there, fascinated. This went on for most of the day. We looked at each other, while those of us apt to be prone to mal de mer went hastily down to their cabins. A few of us lingered on deck, eyeing the sea warily, as the waves roared towards the bow, broke, scattered, as others followed in a steady rhythm. This was mesmerising, but eventually we too went below to the warmth of the comfortable lounge where tea awaited us. The discovery, a solace to some, was the plentiful supply of duty free liquor available at the duty free shop, which had liberal opening hours. But of more interest to me was the news that there was a small library in the corner of the lounge, a few John Galsworthys, also a good selection of the then new, orange Penguin pocket books. Due to our luggage limits, few books had been packed.

Films were shown in the afternoon, evening too, but the sea's movement was a factor; I felt dizziness and nausea sweep over me as the screen moved up and down with each wave. Boat drill was a daily occurrence. This was announced over the ship's loudspeakers each morning, summoning us to scramble out onto the deck. We had to form lines, and wait for the inspection. There would be instructions for manning the lifeboats, and admonitions regarding the constant carrying of our life jackets. This we realized was a good idea, for almost as soon as we boarded, old hands informed us that the convoy that had preceded us by a week or two had been attacked by a group of German submarines. The hospital ship took a direct hit, many hands went down with her, and some of our nurses were lost too. Proceeding in a convoy was sometimes slow going as we zigzagged and changed course fairly frequently to avoid the ever present submarines patrolling. I should mention that for shipboard wear we had been issued with khaki wool trousers and a matching waist length battle dress jacket. As we spent a lot of time walking on the deck, this was a useful addition, and mitigated the cold wind. I liked suddenly looking like a soldier too. Our life jackets proved to be quite a good cushion to sit on once we reached warmer weather.

Towards the end of our sea voyage, as we approached warmer climes, we were escorted, a few of us at a time, down into the stiflingly hot hold. In semi-darkness, we saw our black tin trunks piled high. I noticed, too, as I glanced around, some of the same cargo we had watched being loaded in Glasgow. We called out our names, the trunks were lifted down for us; keys at the ready we opened up to find our tropical whites. Taking these out we replaced them with our grey winter overcoats. Not exactly an easy task, as it was dark and dirty down there. With our arms filled with the white uniforms, white shoes and the white topi almost toppling off, on top of all, we struggled back up the narrow, steep, metal steps to daylight again, and the deck, until we reached our cabins.

It was at this stage that we were at last informed of our destination – not Africa, but India, and docking at Bombay in ten days to two weeks' time. The significance of this secrecy was that word might have reached the enemy, and a submarine sent out to intercept us. Obviously, the crew knew where we were going, but were careful not to divulge this information.

Looking down I noticed that the sea, quite black at this hour, was covered with flotsam, floating towards us, around us, then on and out to sea – Bombay's debris. We became aware as the sun rose that the heat was like none we had ever known before. Even in early morning it was oppressive and something to be reckoned with. Gathering up our hand luggage and wearing our large topis (pith helmets) we went down the gangplanks. It was here that we noticed the porters with a quick gesture were hoisting up our black tin trunks, and placing them onto their heads. They were grinning widely at the expressions on our faces as they set off at a run. Where were they going? Were they stealing them? This happened time after time, incidentally, until we eventually got used to it. They vanished into the crowd and we caught up to them finally, as they deftly packed the trunks onto our train which was to take us to Poona.

It was here that I erred, purchasing a box of chocolates and some bananas from vendors carrying them on their heads. As these had not been seen in wartime England for years (although I admit there had been a very small chocolate ration) I was feeling ‘peckish' and could not resist. Unfortunately, for me, in no time it seemed I began to feel ill. With a shattering headache from the heat, and an upset stomach from my rather rash purchases, I was mercifully sent off to sick bay. Diagnosed as suffering from Poona Tummy, the description given to the illness suffered by a newcomer, I was cared for in the old Victorian hospital in Poona, a relic of the British Raj. It had walls made of very large stone blocks through which the heat scarcely penetrated. I lay in semi-darkness trying to avert my eyes from the fast moving wooden blades of the Punkah fan situated high up in the high ceilinged room. Upon my recovery a day or two later, I emerged still a little weak, but well enough to report back for duty, whereupon I was promptly sent back to rejoin my unit in Bombay to pick up my travel vouchers for Calcutta, and to report to the railway station.

The photo below shows Nursing Sisters on a troop train in India. Sheila is second from left.

A mong the patients who reached us from the Front were a few members of the elite Ghurka Regiment – their fame preceded them. We found them to be highly disciplined; they stood apart from our more familiar Indian troops. The Ghurkas appeared very tough, and insular, although they were always quiet and well-spoken with hospital staff. We nurses were more or less on call all the time as we were so close to the Front with ambulances coming in constantly. The tented, mud-floored operating theatre had an operating table, under the best lights available, which was in more or less constant use, depending upon the situation in the field. We'd go on duty and be told to scrub up straight away as we were expecting another ambulance any minute. I'm sure you can imagine how one had to make an effort, standing upright with the sweat running down one's face in the suffocating 30 degree plus heat; occasionally there would be a thud as one of our number fainted. We had every possible type of trauma to contend with, and fortunately many willing and expert hands. We worked in shifts, and it was heaven to go off duty and have one of our unusual baths with a few buckets of water sluiced over one.

Soon after my arrival at Jorhat the Matron informed us that the Colonel visited fairly frequently and she had accepted the custom of the Indian male nurses to decorate our hospital and grounds accordingly. She was asked for pails of whitewash whereupon they swiftly painted every possible building, possibly an easier alternative to scrubbing them down. But the bit that delighted me the most was the way all the whitewashed paths were bordered with tiny white mounds of earth, each supporting a single fragrant white flower. The sad thing was that the Colonel strode in briskly, looking neither to right nor left, and immediately engaged Matron in a brief conversation about hospital matters. As she took him to Tiffin, I glanced at the hardworking team who had masterminded the decorations, standing at attention in their freshly washed dhotis, but they did not meet my eyes, slowly dispersing to go on with their usual labours.

The photograph below is Sheila in her QA uniform with white cap of a square of white starched muslin, folded in a triangle.

A group of QA nursing sisters, me included, were frequently invited in the evenings to the American Officers Club. This we enjoyed – there was dancing, dining and discovering the rather different American food. In the P.A. shop boxes of chocolates, the coveted American nylon stockings, and other luxuries were available. There was a party nearly every night and this is where I came in; once it was discovered that I preferred lemonade I was quickly assigned the role of designated driver as in, "Where's Cranch? Let's get cracking.” I was in heaven, of course. A jeep, dead easy. You probably know the simple H gear shift. At two or three in the morning we all piled in and we were away. Almost invariably we were the only car on the quiet dusty road, sometimes the great full moon accompanied by myriads of stars leading the way. I thought it was marvellous.

I must mention a very sad scene which stays forever in my memory. Our unit was in a train heading back to Calcutta, and the train had stopped in a siding. As we waited, we noticed a hospital train approaching slowly. Crowding the windows were the Aussies (Australians), recently released prisoners of war held by the Japanese, and they had obviously been badly treated. They were skeletal, emaciated, white-faced, in fact in very bad shape. They attempted a cheer for the nurses; we nearly wept. As the train went slowly on to Calcutta I noticed the bravura Australian hat was at the always jaunty angle. This memory stays . . . I can't forget it.

On a happier note Sheila met her husband to be whilst serving as a QA in India and were married on the 21 July 1945in Bombay, India. She continues:

The war in the South East Asia Command was coming to an end. Troops were pulled back and sent home. On the coast south of Calcutta, Chittagong, in Assam, became a huge encampment for marshalling troops about to return to their own countries. Our hospital unit, all packed and ready to move forward, was given the word to stay put and wait for fresh orders.

Bill was in the R.C.A.F., attached to the radar unit of the R.A.F. Being India it was hot, humid, and steamy. Bill's unit was in a proper barracks, but I was staying in a native type, hastily built basha, put up in a day, with mud floor and bamboo walls and a roof of tree branches. It did have a punkah whirling from the ceiling. Not far off, a similar building with a row of toilets of the outhouse type (generally no toilet paper, one carried one's own, surreptitiously), a simple bucket with a board for a seat. I mention this because I remember Bill was a bit shocked when I casually described the accommodation for the nurses. I didn't really mind at all. I found it all so different from conventional England; this was an exciting new country with new experiences as to climate, scent and smell. My Indian bed, called a charpoy, was made of wood lashed together with coarse string, topped with a webbing of the same string. Our own sleeping bags became the mattress. During the monsoon rains, it rained inside, too, a bit. Anyway, one learned to dodge the drips, and to keep tin trunks and kit up off the ground on bricks, otherwise everything got wet or mouldy.

It was sometimes quite a long wet walk from the bashas to the hospital wards, when at five o'clock the duty shift changed, usually just when the rain appeared to reach its peak, but finally lessening at sundown. So if one didn't wish to arrive soaked to the skin, one required a serious, that is, good, umbrella. Unfortunately, my first one was a disaster. Very pretty, but neither colour-proof nor waterproof, it may have been a sunshade sold to me by a rather unscrupulous bazaar wallah. At the first deluge I was surprised to find the lovely colouring on the shoulders of my smart white uniform. In case you rush to commiserate, this was India, and there were the Indian servants at our disposal. Our kit included our own bath gear consisting of a canvas square with corner straps which slipped over a neat framework which opened up into a support unit. There was a washbasin, too, made of the same khaki canvas, on a higher waist high stand, and a canvas bucket. Each basha hut had a small bathhouse area attached. The bearer carried in buckets of hot water, after one had called "bearer pani jeldi jao,” which means, "bearer bring water quickly”. Later, she came back to dump the water over the floor and it just ran away, and so did she.

We all became used to the tree rats which resembled squirrels, except for their long, narrow, rat-like tails. They lived in the walls and roof of the basha, providing a more or less constant rustle of movement. Once in a while, one would lose his balance or be curious, and leap or fall from the roof with a big wump onto the top of the mosquito net covered bed, making me jump, too.

One day at lunch someone called out, "Cranch (surnames used), do you want to go to a picnic at the beach this afternoon?” "Yes, all right,” I replied in a ‘why not?' sort of voice. A few of us assembled and packed into a jeep. As we arrived I noticed a group of army and air force officers waiting with the provisions for the picnic beside an army truck. All except one, who was struggling to unload a tin bath almost full of boiling water out onto the sand. We all stared; he smiled, but said seriously, "Unless you have a really good fire, it takes a long time for a kettle to boil.”

This was Bill. Bill Jarvis as he told me later. We helped and sure enough, in no time we all had good cups of very hot tea. This water took only a couple of minutes to come to the boil on the fire, which Bill, who was an expert at this, I found out in due time, had made. He told me later that he was a geology student from Canada, accustomed to roughing it, in the bush. After tea, I started wandering along the beach looking for shells; I turned, there was Bill following, and, well, that's how it all began. Our units stayed in Chittagong for some time, then when given leave, some of us planned to go to Puri, south of Calcutta, where there was the famous surfing beach. Bill put in for and was granted leave also. He sent me a jubilant note with his bearer saying, "We're off to the races come Hell or high water,” an expression that was new to me – I liked it. Travelling separately, we met at the hotel and Bill easily obtained a room as it was out of season – the scorching hot weather of southern India. Puri was indeed very hot, and being British, we did go out in the noonday sun where even the sea was hot, well, very warm.

I was in Chittagong when Bill's reaction to receiving his sailing orders was to send me a telegram as follows : "Can you come to Bombay to Harry?” This was a misprint for "marry.” I wondered, as I did know a Harry from the Art School days. We corresponded; he was in India now with the Navy. Was this communication from Harry? What did it mean? But then I realized this of course must be Bill, this was a marriage proposal, yes marriage! I approached Matron explaining the situation, asking for leave on compassionate grounds. Permission was granted. I left at once for the airport. After the usual waiting about for the first flight with a spare seat (anyone in uniform travelled free), I was in the air reaching the airport in Bombay, where Bill found me. He had been haunting the place hopefully for days, scanning all incoming planes. In the taxi on the way to Greens Hotel where they had been holding a room for me, he explained.

it was all happening too quickly, just five weeks after we had met, forced by circumstances, sailing dates, even the war ending. The fact that we might not see each other ever again led me to acquiesce, and so, yes, I did. I agreed. We repaired to Bill's favourite place in Bombay, the India Coffee House, mostly because there were dishes of cashew nuts on all the café style, white marble topped tables, plus all the available newspapers. It had high ceilings with large punkahs whirling constantly, producing an almost cool breeze over the black and white tiled floor. They served excellent hot or iced coffee, the latter in tall glasses with lots of cream on top. We talked and talked, and gazed at each other in some disbelief.

Bill and I went together to see the cathedral in Bombay. I wanted a church wedding, and I had already seen the cathedral from my window at Greens. It stood high on a hill overlooking the Arabian Sea, I didn't know of any other church nearby. We were able to talk to a chaplain who agreed to perform the ceremony, only he suggested that we use one of the small chapels within the cathedral as we were a small wedding group. The date was set, July 21st, and the time, 11:00 a.m., which I thought was suitable because I remembered that my mother had been married at 11:00a.m.

We managed to rearrange our lives accordingly. We had rather a nice apartment in Bombay, once again overlooking the sea which helped a little as it was the monsoon season and still very hot. After some discussion we decided that I should attempt to detach myself from the QUAIMNS/R, in other words, resign from the service. This proved difficult especially as we were in India away from British headquarters. There were numerous letters followed by interviews. Bill was getting more and more worried, determined not to leave me behind, but at the same time being pressured to leave. I was finally given permission to return with Bill to England on the first available boat. This took some time and in the meantime I became pregnant. So not only was I on night duty but having morning sickness too. I explained to the matron in charge and she, although not totally sympathetic to my condition, promised to do what she could. Eventually the word came through that we would be on a boat together in October bound for England. Finally our departure date arrived and we were on our way. Mother, of course, was very excited, Mame too as we were headed for Scotland. Bill and I journeyed from India home through the Mediterranean. This took several weeks. I remember being out of uniform and wearing green linen shorts (cut like a short skirt) on deck. The men produced their khaki shorts, and we all enjoyed ourselves. Finally we reached Portsmouth on a cold November day. After the heat of India this was a bit of a shock. Upon disembarking, shivering in our greatcoats, we were marshalled on to buses and driven through the beautiful beech trees of the New Forest en route to Bournemouth. This is where the air force were being demobbed. There we were sent to temporary quarters in small hotels. I was newly pregnant, and very hungry, and Bill spent most of his time on frequent forays to find shillings for the gas meter, and shopping for the few items of food available without a ration book. He brought me bags of sticky buns which I quickly devoured. The rooms were very cold – I remember crouching around the tiny gas fire wearing our buttoned-up greatcoats, i.e., not just slung around our shoulders.

Once Bill's demob papers were completed, my career in the QUAIMS/R came to an end by mail; copious forms had to be filled in and returned until I was finally freed from the service. We were free to travel to Scotland, where my mother was manager of the Glencoe Hotel.

Below is a photo of Sheila with her husband William Lawrence Jarvis meeting Sheila's mother, Margaret Davison Scott Cranch (nee Hudspeth) in Scotland.

Digboi War Cemetery

Sister Constance Dotterel Mary Wort QAIMNS is buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) Digboi War Cemetery in Assam, India.

Sister Wort died on the 1 May 1945 of acute appendicular abscess in hospital at Digboi India and was interned the next day. She was aged 33 years. Her service number was 209451 and her grave reference number is 4.E.2. She was an SRN and SCM. Sister Wort was the daughter of William and Bessie Annie Wort of Highfield, Southampton. Her gravestone reads:

At the going down of the sun, and in the morning, we will remember them until

Sister Wort is pictured above at the 14th General Hospital July 1942 at the convalescent section. She also served in Burma as she was awarded the Burma Star medal.

Other Nursing Sisters buried in the World War Two Cemeteries in the North East of India include Nurse Edith Florence Turner of the Auxiliary Nursing Service (India) attached 41 IGH who is buried in the Imphal War Cemetery. Nurse Edith Florence Turner died on 4 September 1943.

For more QA graves please visit the War Graves Memorials Nurses page.

The photos above are from the collection of QAIMNS(R) Nursing Sister Joan Cameron who served in India at 127 IGBH Secunderabad during and after the Second World War. She served in Alexandria, Egypt, then Italy. Sister Cameron trained in St Mary's Paddington and joined QAIMNS at the outbreak of WWII. The picture was taken in Italy when she was outside Naples when Vesuvius erupted in 1944 where she remembers the hospital being covered with ash. Sadly she can't remember the name of the other nurse. She was a bridesmaid to a fellow QA's wedding and was later married in Trimulgherry, Hyderabad in August 1946. View this other World War Two India wedding photo on the War Love Stories page.

Partition

Pictured is Marion Fisher Hamilton, known as Maisie, who served during Partition in Northern India in 1946. Her family recall her time there:

Maisie joined the QARANC in 1945. I think she came home in 1947 or 48 after her father died. I know she was at the Station Hospital Ranikhet and in Nowshera, now in Pakistan. She was there during the thick of the violence which followed separation. In one instance, some badly beaten people were admitted to her hospital. Not long afterward, the mob came to the hospital, wanting to get in and kill off the survivors. Maisie stood at the door and denied them entrance and demanded that they disperse, which they did.

I think the hardest for her to bear was the violence around partition. By 1947, most of her patients came from the mobs attacking trains and other travellers. It seemed to her so senseless after the violence of war. I heard about her standing on the hospital steps, refusing access to an armed mob, from visiting former QA friends. She herself never spoke of it. Apparently, she was awarded a medal, but it is not known where it is now. She died in 1968.

Her family also have photographs taken off duty, playing tennis or swimming. She had a holiday in a houseboat on the lake at Srinigar, Kashmir and of temples and even the Taj Mahal so they must have been able to travel.

Dame Louisa Wilkinson

The Matron of BMH Ambala was a prominent QA, Louisa Wilkinson who later became a Dame, formed the QA Association in 1947 and was the first Colonel Commandant and the Director of Army Nursing Services (DANS) of the newly formed QARANC in 1949.

Last QA To Leave India

The last QA to leave India was Dame Monica Johnson in 1947. Dame Johnson was given a carved chest from The Ladies of India to mark the years of nursing service by the QAs. For many years it stood on the first floor of the Headquarters Mess in Aldershot (cited in the book Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps (Famous Regts. S)

Dame Monica later married the Reverence Harry Golding in 1961, the same year she became Colonel Commandant of the QARANC.

Ada Hind

Though Ada Annie Hind was unable to form the IANS due to ill health she led a distinguished nursing career in England and was later able to return abroad to nurse military patients. In February 1885 Ada Hind was a nurse at St. Mary's Hospital, London when she was appointed temporarily for service in the Suez hospitals during the Sudan Invasion. Ada Hind nursed in various locations and was placed in charge of war wounded and disabled being shipped home.

Though Ada Annie Hind was unable to form the IANS due to ill health she led a distinguished nursing career in England and was later able to return abroad to nurse military patients. In February 1885 Ada Hind was a nurse at St. Mary's Hospital, London when she was appointed temporarily for service in the Suez hospitals during the Sudan Invasion. Ada Hind nursed in various locations and was placed in charge of war wounded and disabled being shipped home.

In April 1885 Ada Hind then served aboard the hospital ship SS Iberia and then in September 1885 the SS Ganges.

For her commitment to military nursing Ada Hind was decorated with the Royal Red Cross on her return.

Ada Annie Hind married and her name changed to Ada Yorke.

During World War One Ada Hind became the Matron at Winchester Divisional Red Cross Hospital. During this service she was decorated with a Bar to the Royal Red Cross on the same day that her son, Captain H Yorke, Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) received the Military Cross (MC).

During this period a brother of a patient drew a picture of Ada Hind. If anyone has further information about this image and the artist could they please get in touch.

QARANC.co.uk would like to thank the great grandchild, Alexandra Yorke, of Ada Hind for kind permission to use the photograph of Ada Hind wearing her Royal Red Cross and campaign medals from the Sudan conflict and the additional information.

Tales from the Raj

The actor and comedian Spike Milligan was a child of the Raj. In April 2008 BBC Radio 7 ran a series called More Plain Tales from the Raj to celebrate what would have been the 90th birthday of Spike Milligan. These early recordings were broadcast before episodes of the Goon Show. He described his childhood growing up in India, the son of a serviceman. He recalls the wooden army hospital where he was born in 1918 and conditions in the Raj. Spike Milligan also talked about the high incidence of suicide amongst soldiers who could not cope with Indian life. They would commonly shoot themselves through the roof of the mouth or jump off a ravine. One ravine was guarded at night to prevent such suicides.

The Burma Star Association have published an article about Sister Ivy Pritchard and her time as a Queen Alexandra Nurse in Burma during World War two. It can be read at

www.burmastar.org.uk/ivypric.htm

where she writes about her voyage to India on the The City of Paris boat and working at No 3 Indian British General Hospital in Poona, at Casualty Clearing Stations which included nursing Chindits, the men who had served deep in the jungle with Colonel Wingate, at 38 British General Hospital, Rangoon and at No 3 IBGH.

What Makes A Good Psychiatric Nurse - Mental Health Care in Colonial India

Free Book.

The death of the Brotherhood will be avenged.

RAF gunner Jason Harper and a team of Special Air Service operators are enraged after the death of their brothers by a terrorist drone strike. They fly into south-eastern Yemen on a Black-op mission to gather intelligence and avenge the death of their comrades.

Can they infiltrate the Al-Queda insurgents' camp, stay undetected, and call down their own drone missile strike and get home safely?

Will they all survive to fight another day?

Operation Wrath is a free, fast-paced adventure prequel to the non-stop action The Fence series by military veteran author C.G. Buswell.

Download for free on any device and read today.

This website is not affiliated or endorsed by The Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps (QARANC) or the Ministry of Defence.

» Contact

» Advertise

» QARANC Poppy Pin

» Poppy Lottery

» The Grey Lady Ghost of the Cambridge Military Hospital Novel - a Book by CG Buswell

» The Drummer Boy Novel

» Regimental Cap Badges Paintings

Read our posts on:

Offers

» Army Discounts

» Claim Uniform Washing Tax Rebate For Laundry

» Help For Heroes Discount Code

» Commemorative Cover BFPS 70th anniversary QARANC Association

Present Day

» Become An Army Nurse

» Junior Ranks

» Officer Ranks

» Abbreviations

» Nicknames

» Service Numbers

Ministry of Defence Hospital Units

» MDHU Derriford

» MDHU Frimley Park

» MDHU Northallerton

» MDHU Peterborough

» MDHU Portsmouth

» RCDM Birmingham

» Army Reserve QARANC

Photos

» Florence Nightingale Plaque

» Photographs

Uniform

» Why QA's Wear Grey

» Beret

» Army Medical Services Tartan

» First Time Nurses Wore Trousers AV Anti Vermin Battledress

» TRF Tactical Recognition Flash Badge

» Greatcoat TFNS

» Lapel Pin Badge

» Army School of Psychiatric Nursing Silver Badge

» Cap Badge

» Corps Belt

» ID Bracelet

» Silver War Badge WWI

» Officer's Cloak

» QAIMNSR Tippet

» QAIMNS and Reserve Uniform World War One

» Officer Medal

» Hospital Blues Uniform WW1

Events

» Armed Forces Day

» The Nurses General Dame Maud McCarthy Exhibition Oxford House London

» Edinburgh Fringe Stage Play I'll Tell You This for Nothing - My Mother the War Hero

» Match For Heroes

» Recreated WWI Ward

» Reunions

» Corps Day

» Freedom of Rushmoor

» Re-enactment Groups

» Military Events

» Remembrance

» AMS Carol Service

» QARANC Association Pilgrimage to Singapore and Malaysia 2009

» Doctors and Nurses at War

» War and Medicine Exhibition

» International Conference on Disaster and Military Medicine DiMiMED

» QA Uniform Exhibition Nothe Fort Weymouth

Famous QA's

» Dame Margot Turner

» Dame Maud McCarthy

» Lt Col Maureen Gara

» Military Medal Awards To QAs

» Moment of Truth TV Documentary

» Sean Beech

» Staff Nurse Ella Kate Cooke

Nursing

Nursing Jobs Vacancies UK

International Nurses Day

International Midwife Day

Info

» Search

» Site Map

» Contact

» Other Websites

» Walter Mitty Military Imposters

» The Abandoned Soldier

We are seeking help with some answers to questions sent by readers. These can be found on the Army Nursing page.

» Find QA's

» Jokes

» Merchandise

» Mugs

» Personalised Poster

» Poppy Badges

» Stamp

» Teddy Bears

» Pin Badges

» Wall Plaques

» Fridge Magnet