» Site Map

» Home Page

Historical Info

» Find Friends - Search Old Service and Genealogy Records

» History

» QAIMNS for India

» QAIMNS First World War

» Territorial Force Nursing Service TFNS

» WW1 Soldiers Medical Records

» Field Ambulance No.4

» The Battle of Arras 1917

» The German Advance

» Warlencourt Casualty Clearing Station World War One

» NO 32 CCS Brandhoek - The Battle of Passchendaele

» Chain of Evacuation of Wounded Soldiers

» Allied Advance - Hundred Days Offensive

» Life After War

» Auxiliary Hospitals

» War Graves Nurses

» Book of Remembrance

» Example of Mentioned in Despatches Letter

» Love Stories

» Autograph Book World War One

» World War 1 Letters

» Service Scrapbooks

» QA World War Two

» Africa Second World War

» War Diaries of Sisters

» D Day Normandy Landings

» Belsen Concentration Camp

» Italian Sailor POW Camps India World War Two

» VE Day

» Voluntary Aid Detachment

» National Service

» Korean War

» Gulf War

» Op Telic

» Op Gritrock

» Royal Red Cross Decoration

» Colonels In Chief

» Chief Nursing Officer Army

» Director Army Nursing Services (DANS)

» Colonel Commandant

» Matrons In Chief (QAIMNS)

Follow us on Twitter:

» Grey and Scarlet Corps March

» Order of Precedence

» Motto

» QA Memorial National Arboretum

» NMA Heroes Square Paving Stone

» NMA Nursing Memorial

» Memorial Window

» Stained Glass Window

» Army Medical Services Monument

» Recruitment Posters

» QA Association

» Standard

» QA and AMS Prayer and Hymn

» Books

» Museums

Former Army Hospitals

UK

» Army Chest Unit

» Cowglen Glasgow

» CMH Aldershot

» Colchester

» Craiglockhart

» DKMH Catterick

» Duke of Connaught Unit Northern Ireland

» Endell Street

» First Eastern General Hospital Trinity College Cambridge

» Ghosts

» Hospital Ghosts

» Haslar

» King George Military Hospital Stamford Street London

» QA Centre

» QAMH Millbank

» QEMH Woolwich

» Medical Reception Station Brunei and MRS Kuching Borneo Malaysia

» Military Maternity Hospital Woolwich

» Musgrave Park Belfast

» Netley

» Royal Chelsea Hospital

» Royal Herbert

» Royal Brighton Pavilion Indian Hospital

» School of Physiotherapy

» Station Hospital Ranikhet

» Station Hospital Suez

» Tidworth

» Ghost Hunt at Tidworth Garrison Barracks

» Wheatley

France

» Ambulance Trains

» Hospital Barges

» Ambulance Flotilla

» Hospital Ships

Germany

» Berlin

» Hamburg

» Hannover

» Hostert

» Iserlohn

» Munster

» Rinteln

» Wuppertal

Cyprus

» TPMH RAF Akrotiri

» Dhekelia

» Nicosia

Egypt

» Alexandria

China

» Shanghai

Hong Kong

» Bowen Road

» Mount Kellett

» Wylie Road Kings Park

Malaya

» Kamunting

» Kinrara

» Kluang

» Penang

» Singapore

» Tanglin

» Terendak

Overseas Old British Military Hospitals

» Belize

» Falklands

» Gibraltar

» Kaduna

» Klagenfurt

» BMH Malta

» Nairobi

» Nepal

Middle East

» Benghazi

» Tripoli

Field Hospitals

» Camp Bastion Field Hospital and Medical Treatment Facility MTF Helmand Territory Southern Afghanistan

» TA Field Hospitals and Field Ambulances

D Day Normandy Landings

Details of the army and navy nurses who cared for casualties of the D Day Normandy Landings

The D Day Normandy Landings took place on the 6 June 1944 and was codenamed Operation Overlord. A subsidiary was Operation Neptune. Members of the Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS) and many of the Navy nurses of the QARNNS were there at the frontline to care for Allied casualties and injured Prisoners of War. Rather than repeat information that is already on the website we have added links below to pages with these details which will be of particular help for those seeking information for the forthcoming 70th Anniversary of D Day in 2014.

Two known members of the QAs who were at the D Day landings include Lt Col Maureen Gara RRC and Miss Gill Basant MBE whose memories can be read in Millions Like Us: Women's Lives in War and Peace 1939-1949

Others cared for the injured and ill troops prior to D-Day at the No 1 Combined Training Centre Castle Inveraray, Scotland. This included Sister Jean Ross, pictured above, who served from 1943 to 1945. She was a trained nurse (Dundee) and orthopaedic nurse (Stanmore, Middlx).

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

My PTSD assistance dog, Lynne, and I have written a book about how she helps me with my military Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, anxiety, and depression. I talk about my time in the QAs and the coping strategies I now use to be in my best health.

Along the way, I have had help from various military charities, such as Help for Heroes and The Not Forgotten Association and royalties from this book will go to them and other charities like Bravehound, who paired me with my four-legged best friend.

I talk openly about the death of my son by suicide and the help I got from psychotherapy and counselling and grief charities like The Compassionate Friends.

The author, Damien Lewis, said of Lynne:

"A powerful account of what one dog means to one man on his road to recovery. Both heart-warming and life-affirming. Bravo Chris and Lynne. Bravo Bravehound."

Download.

Buy the Paperback.

This beautiful QARANC Poppy Pin Badge is available from the Royal British Legion Poppy Shop.

For those searching military records, for information on a former nurse of the QAIMNS, QARANC, Royal Red Cross, VAD and other nursing organisations or other military Corps and Regiments, please try Genes Reunited where you can search for ancestors from military records, census, birth, marriages and death certificates as well as over 673 million family trees. At GenesReunited it is free to build your family tree online and is one of the quickest and easiest ways to discover your family history and accessing army service records.

More Information.

Another genealogy website which gives you access to military records and allows you to build a family tree is Find My Past which has a free trial.

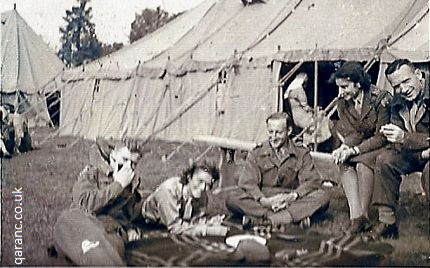

These photos are from the collection of Becky R.Hilda Sharpe who served in Normandy in the days after D-day. She went to France Belgium, Holland and then Germany. She was also at the liberation of Belsen Concentration Camp. She served with the 101 British General Hospital, 81 BGH and 30 BGH.

After World War Two she married Lieutenant Colonel Grainger Wilson Reid Royal Army Medical Corps.

Becky R Hilda Sharpe with Keirl Green Anne and Matron Normandy QAIMNS WWII.

Ship crew with QAIMNS crossing over Bayeux 1944 with 101 British General Hospital.

Sisters Lines at Bayeux in 1944 with 101 BGH.

Waiting for food at Bayeux 1944 101 BGH.

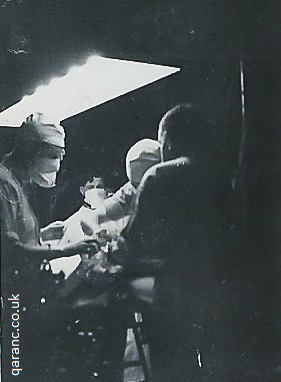

Theatre Tent 101 British General Hospital Bayeux Normandy.

Tent Accommodation for nurses.

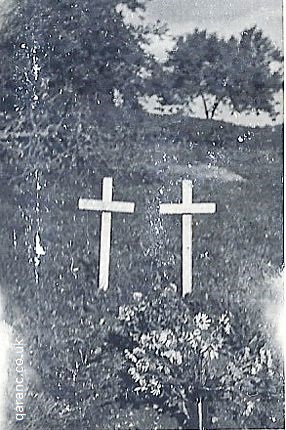

British Graves Beny Bocage Normandy 1944.

Former Royal Air Force Regiment Gunner Jason Harper witnesses a foreign jet fly over his Aberdeenshire home. It is spilling a strange yellow smoke. Minutes later, his wife, Pippa, telephones him, shouting that she needs him. They then get cut off. He sets straight out, unprepared for the nightmare that unfolds during his journey. Everyone seems to want to kill him.

Along the way, he pairs up with fellow survivor Imogen. But she enjoys killing the living dead far too much. Will she kill Jason in her blood thirst? Or will she hinder his journey through this zombie filled dystopian landscape to find his pregnant wife?

The Fence is the first in this series of post-apocalyptic military survival thrillers from the torturous mind of former British army nurse, now horror and science fiction novel writer, C.G. Buswell.

Download Now.

Buy the Paperback.

If you would like to contribute to this page, suggest changes or inclusions to this website or would like to send me a photograph then please e-mail me.

Preparing bandages.

101 British General Hospital Bayeux November 1944.

30 BGH with Brian Brock, Tracey Harrold and Joan Goodchild, Normandy, France 1944.

81 British General Hospital, Oostrum, Holland - R H Sharpe is on the far right.

Hospital Unit Vehicles Crossing The Rhine 4 april 1945 Germany.

Announcement of Victory to Germans being told Luneberg Germany May 1945.

Shillong India May 1946 Sister R Hilda Sharpe QAIMNS.

See more from the collection on the Love Stories, BMH Kaduna and Colchester Military Hospital pages.

Further information about the first medical unit to land via Mulberry Harbour after D Day can be read on the Africa Second World War page.

Other QAIMNS nurses who served in Casualty Clearing Stations and Field Hospitals at Normandy are written about on QA World War Two Nursing and on WWII QA Sister Constance Nash page which includes several wonderful photos including a group photograph at Bayeux and some QAs driving a requisitioned German jeep! There is also the detailed and fascinating diary of Lieutenant Rigby further below.

Patients from D-Day and German POWs were sent back to Great Britain to be nursed at military hospitals such as Netley Hospital.

A Very Private Diary: A Nurse in Wartime

The June 1947 edition of Soldier Magazine has a photo of QA Nursing Sisters Morrison and Bjorkman erecting tents on D-plus-seven. There is also a picture of QAs on a truck just after landing in Normandy to set up the first base hospital (with thanks to Terry Hissey).

If you would like to contribute any info, photographs or share memories of the D Day Normandy Landings and QAIMNS nurses then please contact me.

Pamela Bright served in a Casualty Clearing Station in the Normandy beach-head and wrote about her experiences in her 1953 book Life In Our Hands. She featured in the May 1955 edition of Soldier Magazine which described her time there and through the Netherlands and into Germany. It captures the humour of the British Army towards the QAs during the advance in contrast to the reassurance they gave when the same men came in wounded. One humorous story describes how an infantry officer came to the CSS to look for his wounded soldiers and was overcome by the sights and smells. He was helped to lie down on a stretcher by an orderly and fainted. He woke up back in England! Pamela also wrote about nursing Nazi patients and traitor William Joyce (Lord Haw-Haw). With thanks to Terry Hissey.

Lt Patsy Rigby P/294277 was one of the first QA's to follow the British troops into Normandy and pushed through France and into Germany working in Field Hospitals and Casualty Clearing Stations. Her son, Brian Edmunds, has kindly provided her war diary, which he found after her passing in 1987:

THE FATEFUL YEAR

By Patsy Rigby

If you cherish thoughts of looking glamorous in a uniform, from a woman's point of view, don't join the Forces in Wartime.

Our unit had been chosen to be the first mobile hospital to cross just after D-Day, and so we were to rough it. As one poor lass lamented after she had seen herself in male battledress: "I always wanted to go to Paris, it's been my life's ambition, but just think if I get there now, and looking like this."

After my initial letter requesting to join the Q.A.I.M.N.S/R, I went for an interview, had my medical and was then told that although I had been accepted and would be gazetted in due course, in the meantime nursing staff were desperately needed at an emergency hospital at Arsley, so there I went, in my normal hospital uniform with two others in the same position, and there

I worked hard and happily for several months until we were called to our outfitting base at Hatfield House. Here we were given countless injections, service gas masks and almost daily lectures and instructions. We were taught by a lively little Sergeant how to salute and whom to salute and other army procedure. Since the Q.A.s were now not only Nursing Sisters, but given rank due to their experience, we were to become lowly Lieutenants.

We were sent to London in batches to be measured for our uniforms, grey and scarlet. Two skirts, straight, tunic, peaked cap, gloves and tie, and for ward use, three grey cotton dresses, belted, two short capes with scarlet borders and white veils. With these of course went grey stockings and black shoes. There was also a very heavy but smart greatcoat with scarlet-trimmed collar. I went to Harrods for my uniform and was certainly very well satisfied. The account compared with what it would be today was absurdly small, thirty six pounds, eleven shillings and one penny. Back again at Hatfield House we were issued with a bedding roll and straps, two grey blankets and a small flat pillow. One canvas bucket and one canvas bath and small basin, the legs (wooden) folding, doubling for both basin and bath. One canvas cot with folding legs. We were then told to procure one kitbag, one stove and one lamp, together with one carry-all and some device for hanging things from the tent pole. How very glad I was later that I had disregarded the standard items recommended. Instead of a carry-all I had a small soft-topped suitcase. When I opened the case there was everything to hand, whereas those with carry-alls had to grovel into the depths to find what they needed. While many of the others were lumbered with a very heavy smoky recommended stove, I lit up my valor and the clear blue flame gave out a splendid heat. While their candles blew out in a draught, my small lamp gave a good steady light from its reflector.

Hatfield House itself was a lovely place, still with some of their fine old portraits hanging on the staircase walls and large airy rooms to use as wards, but the Sisters' Mess and above all the toilets and bathrooms were a disgrace. The bathrooms, dark and tiny and very cold were underground on the other side of the road from the Mess. There was hardly room to stand up in your cubicle to undress and of course only the prescribed five inches of hot water could be used, but after all it was only a transient stop, we were all very soon sent to our final units. Four of us were posted to the 81 General Hospital, a 200-bed hospital to operate under canvas. This was at present collecting in a commandeered country home for several weary, cold and hungry months we whiled away the boring days. I was lucky to be sent off twice to nurse in other hospitals, once to the "Head Injurie" in Oxford where, among other things, I learnt that the G.I. orderlies who swept the wards were more highly paid than we were, in spite of spending most of their time leaning on their brooms and gossiping with the patients.

But I also watched many of the head injuries operations and well remember the excellent anesthetist who would allow no talking, in fact no noise at all once he was preparing his patient, emphasizing that the sense of hearing is the last of all to leave the patient as he slips under the anesthetic.

In the ward they were a happy crowd, apart from the poor bemused French Canadian, who having lost the use of speech through his head injury, he was being taught to speak again, but in English.

I was lucky enough to have an Aunt in Oxford, so she very kindly boarded me and fed me very well. I had one amusing experience and the first time I had rank pulled on me. This was in the Mess, as I had had my uniform for several months the very new look had worn off. One of the messing Sisters had been quite friendly with me till one day she happened to ask how long I had been gazetted. When she realized it was only a matter of months she dropped me like a hot brick.

Now we were all called back to the house in Gillsborough where I found we were preparing to go on a "scheme", a try-out to familiarize ourselves with operating under canvas. I was to work in the Officers ward with M, an old campaigner, who had served in Malta, and been torpedoed among other things. She was a Scotswoman and a splendid organizer and we got on very well together. Here we also had our orderlies allotted so as to get to know each other. We also tried out our own 2-bed tents, set up our camp beds comfortably and tried out our lamps and stoves, our canvas wash basins and chairs.

The girl I shared with lived in a dream world of her own and was no help as all in fetching water from the big kitchen Soya stoves or keeping the tent habitable.

That first afternoon on our damp site, my friend Hazel and I wandered off in our free time and eventually found a small farm where a woman sold us half a dozen eggs. We returned in triumph to cook them for our supper and I discovered that I loved scrounging and was good at it.

I would like to record here my very grateful thanks to the old retired Army gentleman who offered baths in rotation to all the Sisters of our unit. It must have cost him a great deal in firing his constant hot water, and it was one of the gestures that I have always felt were very inadequately repaid, for I suppose one day we folded our tents and silently stole away without a backward glance. But, he was one of the people in my life to whom I have always felt very grateful. A hot bath in those days was something to remember.

Once back from our scheme, things began to accelerate. Our tin trunks were brought out and painted with our Unit Flash, the same being stenciled on our bedding rolls and kitbags. Then everything was stacked away again and we were issued with our battledress, men's battledress, so stiff with anti-gas chlorine that they almost stood up on their own. With these went khaki shirts, ties and shoulder pips, ankle boots and dreadful leather gaiters. A large case arrived for us to choose our berets and to my shame, not one fitted my large head. A very large size had to be sent for specially. Tin hats fortunately were always large it seems, these came with netting covers into which one could stick bits of fern or twigs for camouflage.

Excitement rose and of course rumours flew. We were going to Burma, Gibraltar, into Europe, to the south coast of England. Nobody knew. There was a feeling of urgency in the air. Some of us were sent off to give lectures, perish the thought. I was sent to the village hall to instruct half a dozen orderlies in bandaging, this to my horror, as I was always poor at it myself. It was cold in the hall and we were all terribly nervous until I had to show them how to bandage a foot. I looked at their clod-hopper boots; I sighed and took off my own shoe instead. Of course I had a hole in the toe of my stocking, but this broke the ice and by the time we all came back after dinner, we were able to scamper through the rules and methods which they had to know to tackle their exams for up-grading themselves.

Food was poor all the time we were there. Rations were the normal civilian, but cooks were supposed to produce four meals out of these; we were always very hungry and the fact that, for months we had to wear our grey and scarlet, most unsuitable for outside winter wear in the country, so we were generally cold as well.

I think it was in this final day when we had tried on our battledress and were really becoming excited, that B. dropped her bombshell. She would not be coming with us, she and our C.S.M. had had a secret wedding some months previously and she was now pregnant. No wonder she was always dreaming when I shared a tent with her on the “scheme”.

In the middle of May, fully equipped, we clattered stiffly into our trucks and were off. How beautiful the English countryside was, we drank it all in avidly for dear knows where we were going. We drove for hours, the countryside changed, it became sandy with outcrops of pine trees, then we turned into a long drive, flanked by handsome iron gates and before us was a large imposing house with a sailing ship embossed above the doors. This fine house belonged to a wealthy Dutchman, who had offered it, together with its beautiful grounds, as a convalescent home for the wounded. For this it would have been perfect with its well-kept lawns and rose beds, its extensive woods and glades and three lakes. Instead our unimaginative Government had commandeered it as a Commando training centre. Before we arrived, engineers had been billeted there, burhing mines, constructing bridges and erecting assault courses. The fine house was all but ruined. The pillars of the downstairs rooms, although swathed in slats of cardboard, were dented and pierced and the floors beyond repair after the passage of thousands of Army boots. All the toilets were blocked and the hot water system out of action.

Hazel and I once again looked out for ourselves and installed our beds and kitbags in a small room with its own adjacent bathroom. To our disgust this was then commandeered over our heads by the C.O. and we had to move to the colder side of the house. There was a very fine swimming pool in the basement and those of the Unit, who owned or could procure for themselves swimming togs, had a splendid time. The big library had very wisely been locked up and was out of bounds. We now found we had been put on extra combat rations and after our very meager rations of the last few months, the cooks now did us proud and we reveled in good meals.

Hazel and I shared as we shared everything until she was posted away from the Unit at Amiens and our friendship was ended. This is always a dread in Army life, and apart from specially trained personnel or those being moved to better themselves on new courses, seems to me an unnecessary aggravation. As is the very unsettling period when a big boss visits the Unit and everybody knows the outcome will be further moves for somebody. At these times our dread was of a posting to Burma, to the “forgotten Army”, to the heat and insect-infested life. I wonder why the Services think it necessary to keep their personnel in this state of apprehension.

But apart from this background of uncertainty, this interval in my short Army career was idyllic. The grounds of the house were lovely, from the large square goldfish ponds in front of the house, set among formal flower beds, to the three large lakes, ornamented by swans further off in the grounds.

The ground was sandy with young pines growing up small hillocks, leading to almost light moorland with silver birches and ferns intersected everywhere by tracks, typical fox cover, as indeed it proved to be as I saw many a fox slipping away along these trails. I even came face to face with one.

The weather was dry and warm and two of us Sisters decided to sleep out among the pines one night. We made ourselves pine needle and brush beds in the afternoon and that evening slipped out with our grey Army blankets and spent a very good night. Next morning, however, found me in an embarrassing situation. My friend was not on duty that day and being very comfy she refused to come in with me, so I had perforce to go on my own and get in by the only door already open under the leering eye of one of the Company Cooks who took it for granted I had spent the night on the tiles.

We were more or less unrestricted as to where we went or the hours we kept, the whole Unit was on field rations so that the food was good and varied and indeed life was good.

Hazel and I went exploring, at first to the formidable walls and dykes of the “hazards course” lately used by the Commandos who had preceded us, then to saunter along the glades among the acres of pine trees. At last we were in serviceable clothes for the environment, since our battledress stood up to anything. The sun shone and the cuckoos called incessantly and always there was the spice of uncertainty as to what tomorrow would hold.

B was in lodgings in the village and came up to see us sometimes, now a stranger and no longer part of our life. Her place was taken by an older woman, whose name I cannot now even remember since she left us again at Aramanches, being quite unable to stand the gunfire.

All delightful things are only sent to divert us and, alas, all end one day and so we were told to pack up again, get into our transport and be away to another unknown destination, which proved to be Oxford.

Brasenose College it proved to be too, that male stronghold for countless years. With its fantastic ding hall, banner-hung walls and high carved ceiling, embossed with crests, one could hardly eat for gazing on these past glories. We shared this Mess with a Dental Corps (male), but the food was no better in consequence!

Hazel and I shared a large room with bay windows and deep window recesses. It overlooked the High Street and was occupied by a stuffed alligator. This we stood up on its hind legs between our two beds and found it exactly the right height to hold our mugs in its paws, to greet the orderly with our morning cup of tea.

I had this Aunt living in Oxford and was glad of the diversion of going round to visit; also she could keep in touch with my mother once I had left and was not permitted to use the mail! I was taken, too, to meet an Irish cousin and his new young wife. He was a Colonel, but unfortunately I arrived first at the rendezvous and so was able to remove my hat while indoors and was thus saved the tiresome saluting business.

JUNE 6TH D-DAY.

We were all summoned to the Matron's office and told the Allies had landed in Normandy and parachuted behind Le Havre. Suppressed excitement keeps us at bursting point, and it's paradoxical to see everyone here going along just as usual. We are put on three hour passes and at 6pm the C-in-C's message of pride and expectation is read out to us.

Following is an authentic copy of this message:

“ The following message from the Supreme Commander will be read to troops by an officer after embarkation, if prior to 0001 hrs + 1, and only when no postponement of the operation is likely; alternatively, when briefing prior to embarkation after 0001 hrs +D + 1.

“You are soon to be engaged in a great undertaking, the invasion of Europe. Our purpose is to bring about, in company with our Allies, and our comrades on other fronts, the total defeat of Germany. Only by such a complete victory can we free ourselves and our homelands from the fear and threat of Nazi tyranny.”

“A further element of our mission is the liberation of those people of Western Europe now suffering under German oppression.

Before embarking on this operation, I have a personal message for you as to your own individual responsibility, in relation to the inhabitants of our Allied countries.

As a representative of your country, you will be welcomed with deep gratitude by the liberated peoples, who for years have longed for this deliverance. It is of the utmost importance that this feeling of friendliness and goodwill be in no way impaired by careless or indifferent behaviour on your part. By a courteous and considerable demeanour, you can on the other hand do much to strengthen that feeling.

The inhabitants of Nazi-occupied Europe have suffered great privations, and you will find that many of them lack even the barest necessities. You, on the other hand, have been, and will continue to be, provided adequate food, clothing and other necessities. You must not deplete the already meager local stocks of food and other supplies by indiscriminate buying, thereby fostering the “Black Market” which can only increase the hardship of the inhabitants.

The rights of individuals as to their persons and property must be scrupulously respected as though in your own country. You must remember always that these people are our friends and Allies.

I urge each of you to bear constantly in mind that by your actions not only you as an individual, but your country as well, will be judged. By establishing a relationship with the liberated peoples, based on mutual understanding and respect, we shall enlist their wholehearted assistance in the defeat of our own common enemy. Thus we shall lay the foundations for a lasting peace, without which our great effort will have been in vain”?

A few days later I asked if I might have this message, but it was denied me. I had the strong feeling that Matron had never thought of it before as being something exceptional, but now she decided to hang onto it herself. (Later, after many years, the message was published and I was able to get a copy).

At 9pm we joined the other groups at St. Hugh's to hear the King's message and to be told that 4,000 craft are steaming across the Channel, and that weather is poor. Everybody wonders and speculates. Traffic now escalates, the roads are jammed with Army vehicles of every description and there are crowds everywhere. Hazel and I watch from our big windows looking down on the High Street. The weather is dreadful with grey skies and perpetual rain. Food in the Mess is awful, no butter or tinned milk, no coffee, nor any vegetables even. The 45 Dental Officers are very unwelcome, meals take ages to get through and everyone is fidgety and on edge.

My mother comes up from London to spend the weekend with my aunt, so I spend a lot of time over there, dashing back every three hours to report. How the days drag.

On Sunday there was a Church Parade and ironically enough I am not to go as I have no khaki, a year later in Germany only those with grey and scarlet walking-out dress are allowed to go to another parade, a review on the Kiel Canal!

A week later Hazel and I went to the Amateur Dramatics in the evening as we often did. We were in uniform of course all the time. She had a khaki skirt, brown stockings etc. and battledress blouse, but as I had none, I wore battledress trousers. We got into all the entertainments cheaper anyway by being in uniform. We saw Shaw's “St. Joan” that night, which was very well produced. Arriving back in our billets about 10.30pm we found pandemonium. We are to move on tomorrow, what a thrill - valises to be packed and ready by 5am. The waiting has been long and tedious. I find I've never been so glad to be moving on.

June 14th.

Breakfast for the last time in the beautiful dining hall. We are ready in full battle rig to be off by 8.15am. Tin hats with netting covers, gas masks, berets handy, boots, gaiters (leather), arm brassards, Red Cross. We go in our trucks to the station and into special carriages, to Winchester and Eastleigh. What vast organization, moving all those thousands to their correct destinations. From there we get into our open trucks again (3 tonners). Everybody staring at us. As was to become my habit, I positioned myself near the tailboard so that I could see everything all round. Many of the Sisters I noticed just sat and chatted and never looked at a thing, so I didn't feel guilty at always pinching the end seat. We were one of a long convoy interspersed with Dispatch Riders. One of these lads had a bad accident, he collided head-on with oncoming traffic and the Sisters from our second truck gave him first aid, but it was a depressing beginning. We traveled all day and at last entered guarded gates into a wooded area, where an American transit camp was situated. I think it must have been in the New Forest. We checked in, disembarked and were taken further into the woods, down small tracks where we were allotted tents, 4 or 6 of us to a tent on palisades with our own blankets. Presently we were called to a meal in a long mess tent, here we queued with our enamel mugs and mess tins past the American cooks and were ladled out our food. Very good food it was too, such as we hadn't seen for years, but their idea was to put the meat and sweet all together in the one mess tin. I know it all goes the same way in the end, but most of us didn't fancy it and took the peaches and cream in our mugs and returned for the coffee later. White bread and butter too.

Later they treated us to a film show in the evening, of course we were strictly segregated from their troops, but chatted to them as they strolled outside after the show. It was very hot I remember and everyone was very intrigued by the sight of us. They invited us to a boxing match that was to be put on later, but no, it was to be early to bed for us.

After breakfast next day we were all called to Matron's administration tent and given the new red, white and blue paper money and a handful of small change. This put the final seal on our destination (how could we have imagined otherwise?), as it was French money. We were also given sea-sick tablets and the final friendly efficiency, a heavy paper vomit bag!

Off again in our own transport at 8.15am. All along the route people waved and when there was a traffic hold-up they gave us little presents. As we passed through the Security Zones there was only a smattering of inhabitants left. A few women chattering on the pavement as they shopped; they hardly looked up, they had become so used to convoys, until suddenly someone pointed and the word flew- ‘ Our girls are in the convoy'. These women ran to the pavement and waved and cheered us while the tears ran down their faces. We loved them for their concern and felt strangely excited ourselves and somehow responsible to them.

It is a long, long journey; we stopped twice for tea and sandwiches by the side of the road - handed out by Officers who have it all laid on promptly, we never stop long. Presently we reach the outskirts of a shabby city; we never know where we are, hoardings everywhere hide what devastation lies beyond. Still people stop and wave and point us out to others in the road. We wear our Red Cross arm-bands so they all know who we are. Many of them burst into tears. Perhaps we look very young; perhaps it's something to do with their image of us caring for their loved ones over there already. The trucks unload us in a huge darkened shed swarming with troops and equipment. Our small Unit huddles together, overcrowded by this male world. In the gloom it is some time before we realize that one side of this vast shed is really the side of a huge ship drawn close to the quayside. We embark and are sent below and crowded six to a two-berth cabin. I am out of luck here and my portion is the floor, but we are all sleeping in our clothes anyhow. Our first meal aboard is another delight, in the dining saloon the tables are laid with spotless tablecloths and gleaming silver and glass, what luxury! This food I have no recollection of, it was the gleaming tables that captivated me and to be served by stewards.

We were chased off to bed after this, down to our over-warm cabins where, with the help of two seasick tablets, I slept very well in spite of the quiet intensity of the swarming fleet all around us.

We sailed quietly off at 4.30am, one of a huge convoy with a great many aboard. Strange, I never thought of the possibility of a torpedoing, my mind was leaping forward with anticipation of reaching the other side.

June 16th.

Still very warm weather. It seems a very long crossing. As we stand on the top deck there are boats as far as the eye can see - a sight too immense really to take in. I try to think to myself, “This is part of the most vast armada in history, look and remember everything”, but I am really too battered by impressions to realise what I am a part of. Instead, Hazel and I laugh and chat with two young apprentice lads who are painting the life-boat. They have red paint and paint our names on our enamel mugs. They lark about and jump across the gap from the ship's side into the boat. The same is happening on the deck below and without warning there goes up the cry, “Man Overboard”. A young boy has fallen between the ship and life-boat. The sea is grey and a little rough. A slim corvette, our escort, hurries up out of line and the rumours fly, she is searching for the lad, she has picked him up, no he is never found; no-one can spare the time for one foolhardy boy. We never heard the true outcome, only the intercom buzzes and a sharp authoritative voice warns apprentices in future to wear life jackets constantly. We turn away from the rail, deflated and somehow feeling guilty. Boat drill now follows in full kit as well as Mae West life jackets. The slow hours pass and we wonder what will be in store for us over there and how we will personally handle it.

Towards evening, while the coastline is still only a low smudge in the distance, several landing craft come alongside. Some are merely rusty-sided lease-lend hollow hunks and we stare down at their emptiness in disbelieving gloom - would we really disembark into things like that to be shuttled ashore? The sea had turned roughish and the convoy had stopped, the smaller boats pitching about uneasily. We stand watching and waiting, fully laden, while the Powers That Be changed their minds again and again. Eventually at 7.30pm scrambling nets are thrown over the side of our “Castle” liner, and then a very small craft hauled alongside. We gaze down in consternation, at the net half under the water and at the small craft surging up and down so far below, but there was no help for it, over we must go and don't for God's sake be such a fool as to miss a footing. Heavily we fumbled our way down, stiff new boots, stiff gaiters, banging gas mask and slipping tin hat, but thankfully we were grabbed into the heaving boat below, where we jammed the sides and waited for our full compliment. What happened to the other troops on board the liner I have no idea, I never looked back. Whether it was the excitement or the two seasick tablets, I don't know, but I was not even squeamish, terrible sailor that I am!

Quickly we headed towards a distant shoreline, the shallow water and beaches strewn with hulks, debris and broken tanks. Spars of tank traps reared out of the oily water. We landed straight onto a shingly beach (still of course encumbered with Mae West's, tin hats, gas mask and all the rest of our attractive gear). The few troops who greeted us were cheery, but disgusted we had brought no newspapers with us. We were assembled again in a field and food was passed round. I was sent to collect the Mae West's, now finished with, and needed back at the boat for other parties. Someone pointed out a ruined tower from where a German sniper had wreaked havoc before he was eventually shot himself. So at last, into our trucks again and we moved off between white tapes (denoting tracks cleared of mines), into the gathering darkness. Distant and continuous gunfire and bombardment throbbed the air, punctuated by flashes, while beautiful tracer bullets arched across the sky. It had been a long day indeed and we nodded in our seats. At one time our two trucks stopped; the leading driver had lost his way and was in a panic, declaring he was driving into enemy-held territory. He turned round as best he could, feeling his way in the blackout with hooded lights, yelled at the following driver to do the same and we scuttled back to the last crossroads to study the signs again. At 1.30am we at last arrived at the field allocated to our Unit where familiar faces greeted us and hot drinks, those marvelous self-heating tins of soup and cocoa, were handed round. H.E. was there, very pleased to see me, on the scrounge for cigarettes as usual. In darkness we scrambled into tents, five in a two-man tent, and on stretchers rolled in our blankets, dead beat, but thankful to have arrived.

ARROMANCHES

June 17th.

Onto the wards at 8am, in our battle-dress, but minus our stiff boots and gaiters at last. Now we could see the layout of the hospital more or less. We were spread along a flat field with rising ground behind and a small coppice. Ambulances and other vehicles came through a check-point at the entrance to the field and were directed first to clearing and admission tent. Here casualties were expertly sorted out as to the severity of their injuries - whatever their nationality. Medical cases went to the medical tents, but casualties were sorted for immediate surgery, or for Officers or Head Injuries Wards. The long double line of brown tents stretched back towards our mess tent and sleeping tents, and further towards the rising ground were the “cook houses'. Everything, the Theatres and Church included, were under canvas. Our latrines were across a ditch and through a hedge, and consisted just of canvas screens round the usual “thunder boxes”. Unpleasant in wet weather.

I was sent to the Officers Ward with M again (who was later to be sent to India). We had two large marquee-type tents and one small 2-bed tent which was reserved for General Montgomery should he ever become a casualty. Behind these large tents were additional lean-tos. One served as a sluice room and the other for receiving meals from the Company cookhouse and distributing them, as the primus stoves were there for heating up drinks etc, so this corner was also our sterilizing “room” with a small autoclave.

All the tents had heavy canvas “floors”, with a spare strip of canvas we portioned off an office by the door for our own use. Here we kept all the patients' documents and wrote up charts and evacuation data. M always had a very well run ward. All the ward beds could be folded and stacked when necessary, every single piece of equipment we carried with us on our very frequent moves. Part of our function as a 200-bed hospital was to leap-frog forward the Casualty Clearing Stations, taking over from them while they, being smaller and more concentrated, moved on again.

Our orderlies, who had been coping on their own since D-Day, were very relieved to see us; it had been a trying responsibility for them. When we arrived there were very few beds up, they just hadn't had the time, but the floor was cluttered with stretchers. Two more pairs of hands soon made all the difference and mattresses and bedding were unrolled and patients not being evacuated at once could have the comfort of a bed. Men were evacuated to the U.K. by boat daily and of course more were admitted at any time. I could soon laugh at my first reaction to admittance straight from theatre. “Why weren't we warned?” I asked, almost indignantly, but of course there was no phone. When the theatre had finished with a case the Pioneers brought the stretcher straight to its assigned ward, together with a very hastily scribbled note in the patient's case envelope. This might simply state “G.S.W. (gun shot wound) of R. Elbow” together with a quick diagram of the fractured joint and its repair. The whole thing would be in heavy plaster, often with the fractured joint diagrammed again on the cast and the man was ready for evacuation the following day. Any casualties who could hopefully return to duty, fairly soon and any of the S.I. or D.I. (seriously ill or dangerously ill) we would hang on to. It was a very efficient system.

M and I started off that first morning with the admission book to make a fast round of our Officers and the few Other Ranks in our second tent. I was glad to find I could cope with one or two more comfortably than she did. One young Captain had been shot in the face and he was just coming round from his anesthetic with his wet and slobbery mouth bandages he looked a real mess, M passed him quickly by, but as I had done plastic surgery before I could see that he would eventually mend well. I told him so at once, helped him sit up and have a drink and brought out the office mirror as he wanted to see the damage at once. All this allayed his fears and he was soon as chirpy as possible.

Strangely enough, this, my first patient in Normandy, was I think the only one I ever saw later. He must have been on leave at the same time as I was many months later. My mother and I were in Hyde Park looking at a wrecked German plane on view there and I recognized this same Captain with a pretty girl on his arm. His facial injuries had healed well. I did not make myself known.

We spent the whole day organizing the ward. M was extremely good at this and soon simplified the orderlies work enormously. We discovered that for some reason, some odd quirk of human nature no doubt, however we arranged something at first that arrangement was always adhered to forever after. I think one does this in civilian life too. M got hold of some material and we made curtains for each locker. It was amazing how such small touches cheered the men and pleased them very much. Our second (overflow) tent which was filled with Other Ranks, mostly medical cases, would soon be re-absorbed into their units. They were mostly flare-ups of malaria etc. These we treated exactly the same as the Officers in respect of small comforts.

We did have rather unpleasant incidents, one from our ward that wasn't so important. We had a Prisoner Of War doctor, and when he was on his evacuation stretcher one of the Pioneers tried to get his jack-boots away from him. I objected because it seemed wrong to me to take property from a man unable to defend his personal effects. When I went out to the ambulance to settle a load aboard, this P.O.W. told me his boots had been taken again. Although I got them back, I realized that sooner or later they would be stolen, especially as this man wasn't a very pleasant character, and that's human nature, not to feel guilty if you don't like the individual.

The second incident was far more serious and amazed as well as angered us.

Several Medical Students were sent out from U.K. to help us. I never saw any, but Hazel, who was on the Head Injuries Ward, knew all about them. Apparently there were several cases of thieving from unconscious patients' belongings, money, watches, good cigarettes, lighters, etc. Not only was it a despicable thing to do, but it put suspicions on our Sisters and Orderlies.

Thankfully, many of the missing articles were found in the student's luggage and they were all sent home.

That first day was crammed with evacuations and admissions. We kept them warm, repacked dressings where necessary, gave injections and noted these on the medical cards which went with each patient. We fed them when time allowed, and sent them off again. We worked all day with only a quick snack grabbed from our “cook tent” at the back, until 9.30pm, when we staggered off duty, tired and hot. Our own tent had been put up meantime (although in the months to come we had to put them up ourselves). Hazel and I shared, and had dumped our kit at the very end of the line to indicate where we intended to ‘camp'. As far away from authority as possible, that was our motto! We hung our candles and lamps (with reflectors) from the centre pole and got out our small stoves, for heating water for warmth. Each of us had a canvas folding bucket, chair and bath, and our camp beds for sleeping. There was very little water, one bucket a day for all purposes.

Some time here I acquired two valuable additions to my possessions. One day I noticed that the blankets on some of the stretchers were not our regulation Army ones. On asking the stretcher bearers, they told me the dark green ones were U.S. Navy and the bright brown ones were U.S. Army, they also said that as long as they had their correct quota of blankets, it made no difference to them if I wanted to swap mine. Both these blankets were very good quality and much softer than our Army issue, so I was delighted. These blankets were evidently very durable for I still have the Navy one in use over forty years later and bits of the Army one as pets' blankets.

My other possession was a pair of boots, acquired in this way: They were on the floor beside a young Canadian's bed in the ward. I think they were a little small for him, they had leather uppers and long canvas legs, reaching up to the knee rather like a riding boot. “If you get hold of a pair of British Army boots in my size” said he, “then you can have my boots in exchange”. So off I went to the QM Stores where, not only were there new spares, but also boots discarded by stretcher-borne wounded men, so that there was a good selection and of course I got my long Canadian boots!

Nothing to do with boots or blankets, but a small incident which amused me highly. As I have described, our ward tents faced each other, leaving a wide ambulance track in between. One morning there was the sound of a small plane very low and flying very fast. It was too low among the tents for the ack-ack to dare to aim at it, but they were all blazing away to make a frightening noise. All the patients of course were avid with curiosity as to what was going on and so was I! So I went to the door of the tent to look out and report back. “Better come inside” said M, “you might get hit”. Fair enough, but what protection was a stretch of canvas when you come to think of it, and we both laughed.

In the Sisters' Mess we had two splendid orderlies, Baker and Pemberthy and at whatever hour you appeared, hungry and tired, they could always produce something hot, they were always watching out. There was no bread those first weeks, just large biscuits, jam, butter, porridge, sausages and bacon, all tinned. H.E. was our Sisters' personal cook and managed many varied meals, all originating from the “compo” rations. (Rations for so many for 24 hours). We still had our individual 24 hour emergency tins of food which we had humped along with us, these contained, as far as I can remember, reinforced chocolate, boiled sweets, 3-in-1 tea pack (dry), pemmican and a delicious compressed porridge and sugar block, and cigarettes. I swapped my cigarette allowance for this as many people didn't like it.

The nights were very noisy with gunfire and shrapnel, the ground heaved from heavy explosions, but how safe one felt in bed with one's head under the blankets! An illusion of course, well demonstrated for us when two Sisters from a C.C.S. were injured, one being evacuated with an amputated finger and penetrating wound of the chest.

June 20th.

The weather has now changed and become cold and blustery. We were not quite so busy and were given our very first off-duty 1 ½ hours. On this day, too, air evacuations began. The R.A.F. had made themselves a small landing strip somewhere up on the higher ground just behind us. This of course also necessitated the presence of ack-ack guns and drew fire from the enemy. All this made the nights even less pleasant. Two of our Sisters left us here; one was the elderly Sister whose name I never knew. I have no idea who picked her for this type of work as she became nearly hysterical with fright after the first few noisy nights. Possible she had never been through the London Blitz as most of us had, as our baptism by fire. The other was a very charming and efficient Theatre Sister, a married girl, who now found herself pregnant.

Generally chest wounds were not allowed to be evacuated by air, but one man I remember was passed for air travel on condition we could get off the strapping right around his chest, but of course he was one of the most hairy men I have ever encountered. He was so keen for a quick evacuation that I set to, and a very agonizing job it proved for both of us. Should I rip fast, or snip carefully after lifting an edge of strapping? Even swabbing with surgical spirit failed to part the stuff from his hair. In the end, by employing a little of each method, I had him free, and away he went.

That evening we were off duty at last by 8pm. distant gunfire continuous and as always louder at night. I kept a very small diary and when I wasn't too tired to write it up, found it kept a good check on my days.

June 27th.

We admitted several bad cases, one of them a huge Scotsman, 6ft 3in, with a broken back and paralysed from the waist down. He had been in a jeep accident and had been thrown out against a wall. He kept on asking for fruit, of which we had none at all.

June 28th.

This day I was lucky enough to get some off-duty and to get the chance of a lift in to Bayeux in the laundry truck. Hazel had arranged it as she was friendly with the driver and she came too. We found the road crowded with every type of vehicle. Div. signs in bright colours at all turnings or cross roads. The town itself had cobbled streets and a lovely Cathedral where William the Conqueror prayed for success before leaving to invade England. We went to several shops where I tried out my very inadequate French, hoping to buy fruit. The dairies were real dairies, small tiled shops generally with a marble counter, very clean and cool. There was plenty of butter, cheese and cream. We met the driver and had an ersatz coffee in a small dark café and then headed for a market garden we had been directed to, where I bought 2kilos of cherries for 40 francs, for the Scotsman.

June 29th.

Today the Scotsman was taken to the Theatre for a plaster cast so that he could be evacuated. He did manage a few cherries after coming round, but I feared he was much worse after all the handling. Presently he became paralysed from the neck down and although we tried artificial respiration and oxygen, he died soon after 10pm.

I had my first death in the ward the day before, a man with a very bad head injury came to us straight from Theatre. He was quite yellow (although this could have been due to malaria treatment). His respirations were very loud and stentorious and seemed to fill the whole tent. He never regained consciousness and when he died the relief from his gasping breathe was great. I began washing the body preparatory to laying him out, but our head orderly came up with a grey blanket and very tactfully showed me how to roll the body tightly in a supine position with arms crossed, the blanket held in place with large safety pins. The body was then covered with a large Union Jack ready for the Pioneers to take it away,

We now had a great many head injuries due to a new weapon the enemy was using, the bazooka of ill fame. These cases overflowed from the usual Head Injuries Ward and we had to borrow a Sister from another tented hospital in the vicinity, the 75th Gen. Hospital. This hospital had just arrived and set itself up in a field adjacent to us. For some reason I cannot remember, the Sister was quite useless, so we politely returned her.

June 30th.

This day we had a visit from General Montgomery. We Sisters were lined up in front of our Officers' tent and were introduced. I'm sure we didn't wear our berets (as of course we didn't wear them on duty), for I certainly don't remember having to salute! He arrived in a jeep, escorted by a second jeep fairly bristling with “Red Caps” (Military Police), five of them, all fully armed and with eyes everywhere. “Monty” looked exactly like his pictures, gave each of us a firm handshake and a piercing scrutiny from his grey-blue eyes. He did not inspect the little tent perhaps destined for his occupation!

Instead, we were later to admit a civilian woman casualty into this same tent. Civilian casualties were heavy from strafing on the roads, poor homeless refugees packed together as they struggled on from one bombed-out village to the next, carrying their bundles and babies. All that this woman possessed, apart from her clothes, was a scribbled note to say that her husband had gone on to the next town. She had an injury and when she came to us from Theatre she appeared to be speechless. M and I had great difficulty in making her understand our poor French. Every time we tried to encourage her to use a bed pan she struggled to get out of bed, so we stood stupidly by repeating “La toilet, Madam” and yet refusing to allow her out of bed. Poor woman, being an ordinary peasant, she would never have seen such a contraption!

July 2nd.

Very heavy thundery weather with rain by evening. I was off duty at 5pm and did some washing. This chore was affected by heating some water over the primus stove in a very small pan and adding it to cold water in the canvas bucket. The clothes we hung to dry on the guy ropes. We did have small flat irons which could be heated over the stove and we could iron a few oddments on top of a suitcase. As all water was at a premium, we didn't do much washing!

“Madam” was improving, and one day she sat up in bed holding her bandaged head and crying “Oh la la”. I reported this in my day report as it was cheering to know she really could speak after all, but it sounded rather absurd in the report and gave us all a good laugh. A few days later I was detailed to accompany her in the field ambulance to Bayeux Civilian Clearing Station. As we went along I had time to prepare my introduction in French and I actually trotted it out to the Nun who received us in a vast bare hall crowded with civilians, injured or homeless or just visiting. However, I was floored instantly by her flood of inquiries in answer, and collapsed into silence. In this big hall the injured men and women were lying in rows on stretchers. Without any false modesty, there and then the Nun stripped Madam naked of our pyjamas, shoved her into a voluminous nightgown, bundled up our blankets and I was on my way back.

July 3rd. The weather broke with pelting rain.

July 7th.

A large number of Canadians have arrived and dug themselves into fox-holes in the woods and fields behind us. The nights have become very noisy indeed, with some bombs and very loud ack-ack. We now have a battery on the hill just behind us, only a few hundred yards away. Tracer lines criss-cross the sky, looking bright and beautiful. The ground shakes and the air batters, yet one feel so safe once one dives into bed. The only time I can really say I felt alarmed was when I used to slip into the tent I shared with Hazel and the tent flaps began battering loudly with the concussion. You see, most us had already nursed in big hospitals in cities constantly bombed and the noise and vibrations were nothing new to us.

Our camp beds are now down about 2 feet into the ground, some pretty hard digging for our poor Pioneers to achieve this. It brings us down to sleeping practically at ground level which, to our way of thinking, is possibly more dangerous. However, jump into bed, pull up the blankets and ‘safe' and snug, you are asleep at once.

During the day there was a majestic sight, fleets of hundreds of planes passing over to bomb Caen. Being so near to the coast we saw them arriving, going in to bomb, turning round and going back over the sea, a continuous droning, with many planes hit. When a plane is hit it disintegrates so slowly. A wing, or some unrecognizable part, will sail quietly out and drift so seemingly slowly down. Even a bursting plane, when seen from a distance, is destruction in slow motion in the air, only appearing to gain horrifying momentum as it neared the ground. Parachutes drifted out like white mushrooms. Our Pioneers (our only armed members) were almost un-controllable with excitement. For some reason they assumed all parachutes bore enemy airmen and were avid for action against them!

July 9th.

Outskirts of Caen taken, though we never guessed the final capture would take so long.

Today I heard my cousin, Arthur St.George, had been killed on June 16th. I grieved for his mother in Ireland.

We weren't very busy now. The battle had moved on, and someone else had leap-frogged over us. We went for a walk through the rough orchard behind us, where there is a donkey tied out to feed. It had got the rope tangled round its tree so I was leading it round the opposite way to free it when a young man appeared from nowhere, very possessively. However, when he saw my intention he let well alone at once. There was also a draft mare and foal among the trees there, both their rumps and sides clipped by shrapnel splinters. We watched them when a raid began and saw them run to shelter under the trees where they waited patiently, making themselves as small as possible, poor things. Out of the gate at the far end and along a track through cornfields, there was a radar station. As we went along, men would pop out of ditches or shelters to stare and marvel at a “white woman”. I felt horribly conspicuous and loutish in battledress, most inadequate even to be called a woman! All the roads and lanes were so thick with white powdery dust, it lay along the hedgerows like snow, through which roses bloomed mistily here and there.

Caen taken at last. I was off duty from 10am till 1pm and we went for our first real bath. Several of us went in a small truck and it was, as usual, very dusty. Our driver lost his way trying to find the Beach Group so that we went all along the sea front, seeing great destruction. Boats were thrown up on the beach and twisted iron girders rose to the sky everywhere. We also passed an airplane repair works. Eventually we found the Beach Group's quarters, a good large house. The Group Commander told us he had picked this out on the map and marked it as their future quarters even before D-Day. When they got to the house they found the old couple who owned it dead in bed. Whether they had had enough and could stand no more when the invasion came, or whether they had tolerated or possibly even helped the occupying forces and were now afraid of retribution, who can say. I believe they had a son in England.

For our baths, hot water was boiled up in Soya cookers in the grounds and carried up in buckets by the men of the Beach Group who wouldn't even accept cigarettes in exchange for their hard work. We took turns going upstairs to bath, two at a time, in the meantime being entertained by the Beach Group personnel. The C.O. I remember, read us “The Specialist” in dialect, the first time and the best rendering I have ever heard. One of the young men took me over the old house and from the attic I noticed a small white toy dog which came right through the following twelve months with me, riding at the top of my kitbag, with his head poking out!

July 13th.

I had half a day off, it was very hot again. I borrowed a khaki skirt and stockings and H and I went into Bayeux. We went into the Cathedral which, alas, I cannot remember at all now, except for the fact that there was a very good reproduction of the Bayeux Tapestries along the wall. The originals had been worked by the women of the City and depicted William the Conqueror's departure to invade England. To get into Bayeux we ‘hitch-hiked' (though such jargon had not been thought of then). We just waited till a passing truck picked us up, and the same to return, no trouble.

In the evening it was still very heavy and hot. We stood under the trees beyond our camp and watched the Canadians going up to the front line in a very long convoy. It was distressing, for they seemed terribly young and inexperienced and looked horribly forlorn and tense. History was to prove that they were too inexperienced and there was dreadful slaughter.

July 14th.

All the Canadians have moved out, leaving a dreadful mess of tins, bits of ground sheet and paper behind in their foxholes. Some of these were very well made and roomy with branch roofs etc. Some were mere slits. There were “dog fights” in the evening. I saw one plane down and the parachute drifting out; another jettisoned two petrol tanks, one in our field and the other landed on the guard tent of the 84 Gen. Hospital behind us, killing the occupant. A very noisy night indeed, bombs and flak and the usual rushing noises and concussions.

Some time before this an Irish Sister was sent home as couldn't stand up to it and prayed all the time.

Dame Katherine (Matron In Chief) arrived on a visit to our next-door neighbours (the 84G.H.). Her advent leads to transfers and is looked on with dread.

We now have a larger tent for other ranks to house medical cases, mostly malaria recurrence. Nearly all are quickly evacuated. I had been sent a large bundle of ‘comics', Korky the Cat, Donald Duck, etc and bore them in triumph to the Officers Ward, where I offered them round. A rather shocked superior silence greeted this gesture, but as soon as I threatened to take them straight to the men next door, eager hands were waving and soon every Officer was happily giggling away. Once they had done the rounds, of course, our Other Ranks had their turn.

My mother also sent me a loaf of white bread, rather mouldy on the outside, but much appreciated after so long on Army biscuits.

About this time we received another young Lieutenant, paralysed from the waist down. He is very cheerful and has no apprehension at all since his own mother suffered the same disablement after a riding accident and eventually recovered. Alas we are not as optimistic. I have often thought about him since and wondered if his mother's accident happened so that she could gain the experience to help him later. Stranger things have happened.

Round about this time, our ward gave hospitality to a group of shipwrecked Americans. None had been injured but they assure us they will all qualify for the Purple Heart Award. They were outfitted in the weirdest assortment of clothes you could possibly imagine, which gave our Officers many a laugh. A cheery lot who didn't stay long.

We have had a Colonel with a G.S.W. of hand. This man became fed up with waiting around and with the threat of being evacuated, and discharged himself to go and rejoin his Unit, driving his own jeep. We privately thought well of him, though medically we were conditioned to think he had ‘sinned' badly in deciding his own future instead of conforming to correct procedure and, as I say, probably being tamely evacuated to the U.K. and possibly never catching up with his Unit again.

We came out of our tents one morning to find leaflets (dropped by night planes) scattered over our area. I still have many examples of these, some green, some orange. Both sides were represented (I wonder how both participants chose the same night). The propaganda was equally poor. The idea was for a fighting man to approach the enemy waving his pamphlet and to be instantly welcomed as a comrade. (I wouldn't have risked it, however desperate I was!).

Other enemy printed matter I collected as we went about was a booklet and sketches of the Russian Front and several song sheets. Wandering one day we came upon a gun emplacement overlooking a road. There had been a direct hit on the crews' living quarters, strongly entrenched though they were. Among the rubble and mass of scattered papers was a smashed upright piano and from here I collected several German song sheets. Later, at Falais, I was to find some more; some sentimental, some patriotic to the enth degree.

Another morning when we got up, the trees and countryside was festooned with bright glittering bunches of silver fibres. This we heard was a device to be-fuddle radar when raiding planes were going over, well maybe, but it was startling and a matter of delighted wonder for those of us on the ground.

Among the dust and debris of War, we walked through, the small hamlet on the other side of the long orchard. I spoke to an old couple living in an untouched rose-covered cottage (everything thickly coated with dust from passing convoys of course). They had two young grandchildren living with them and appeared quite contented to have survived at least. The farms were of poor quality, in one tumbled down orchard, near the farm buildings were an enormous lean and vicious-looking razor-backed boar. No cattle or riding horses here, though we came across several fine specimens of the latter later on. These had been German Officers' mounts and our Officers were now using them for recreation.

July 22nd.

An invitation came for several of us to go to an R.A.F. show some miles off. We were given transport and arrived in a field where drinks were provided from a large marquee tent. Our hosts came out to meet us and I think I was lucky in being selected by a quiet Officer, probably in his early 40s, a little older than the general run of crazy young men. We walked over to a large barn, a beautiful old red brick structure which had probably been the pride of many generations of farmers. They put on a good show with community singing with accordion accompaniment. Then there was a comic and his stooge. This man had the biggest mouth I have ever seen and used it to marvelous effect, but without saying a word. He was followed by a contortionist, a man with a beautifully tattooed snake winding right up one arm. By twisting and contorting himself he brought this snake into play as if it were alive. Altogether it was a lively and happy evening and we were home by 11.30pm. Some of the Sisters returned very much late by private transport, but all were up to go to duty next day.

We came upon many strange things during our wandering in off-duty periods. Once, going a bit further afield than previously, we came down the side of a copse pocked with many small slit trenches and as we walked round the side of the hill, the plain stretched before us, it was one vast area swarming with thousands of P.O.W.S, rather inadequately held in hastily thrown up wire enclosures and lightly guarded. We stared in amazement from our hidden position, we had never seen so many thousands of men penned together and had no idea so many prisoners had been captured. Did they all submit docilely to capture I wonder, or were there many escapes?

Another day as we walked towards the cornfields, we heard the approach of tanks and presently several of these ungainly monsters churned their way towards us through the dust, evidently coming from the beach areas, but these were tanks with a difference, each had a thick metal bar protruding well in front (in the nature of a car's bumper bar) except that these had short lengths of heavy chain wrapped round them. When in action these bars rotated and the chains flailed the ground in front of the tanks and were to be used to clear tracks and roads of mines and personnel booby traps. Which also reminds me, once we were coming through a pine wood, and there on a broken-off branch at convenient height was a small mirror and a shaving brush! Was someone called to alert in mid-shave, or had it been left there as a booby trap? We didn't investigate, but left it alone.

A very comical sight which delighted us was occasioned once when we had wandered up a hill near the ack-ack battery. Some of the RAF men had assembled one of those bicycles which could be dropped by parachute. They were tiny, though doubtless very strong. This time a very chubby man was trying it out. The combination of this very small bike and this very rotund chap was altogether ludicrous as he struggled along the well-worn track through the fields.

There was one German gun emplacement built of very thick concrete on the side of a hill facing seawards where we often wandered. It was dark and smelly inside but had a certain fascination and the short grass of the hillside was fresh and sunny; as I say, we had often been there, wandering at will. However, one day to our surprise we could see a Dispatch Rider riding round and round the area and the small copse nearby. We then saw a large new notice, “Mines” and that there was a path bordered by white tapes leading directly to the emplacement. Oh well, you never knew did you! It was from here that once during very thundery weather some time after we arrived, we looked out over the distant bay where one could see the big silver barrage balloons floating majestically above boats and stores and ack-ack guns. Towards evening we watched the lightening of an electrical storm strike those huge balloons which erupted in flames. They writhed and belched, then crumpled and fell out of sight. Once hit by lightening it would presumably be very dangerous to cut the cable and let them loose. A great many were destroyed in this way.

I was lucky enough to be invited by a Beach Group with a few other Sisters to go and see the Mulberry, that incredible floating dock which had been towed across the Channel from England and which did sterling service until practically destroyed by a very bad storm. It was from the Mulberry that hundreds of our wounded men embarked for hospitals at home. A very thin track wobbled over moored barges leading from the beach to this huge structure. I had asked our Ambulance Driver about this journey and some confessed to feeling very apprehensive and even squeamish when driving over this moving causeway, but it was safe enough. Fortunately we did not have to go this way; we were taken by motorboat and climbed up an iron ladder to the decking of the pier. Many ships were moored to the far side, discharging or embarking a great variety of things, among them was a shipload from Canada, disembarking Canadian troops and Army Nurses. These were in full kit (as we had been) complete with gas masks and tin hats. We felt very superior, as old hands, in battledress and berets!

We were taken back to the Officers' Mess for a meal and then hurried away as the evenings' artificial fog was due to be let loose on the area and presumably roads were then difficult to navigate. I would very much like to have heard more about this device, but I suspect it was hush-hush.

August 2nd.

We have orders to pack up, as we are to move forward this Saturday on Monday. Nobody (except I suppose our superiors) knows where we will be going. Many tents are down already, but we still have our men and four Officers left.

Although in the months to come we were to pack up and move on many times, this was our very first experience of it and our orderlies were the greatest help, having done the initial unpacking before we arrived. The procedure was as follows:

Each mattress was rolled tightly round two pillows and shoved into a sacking holder. The linen and blankets were neatly folded separately and put in their holders. Beds, as they were vacated, were folded and stacked. The kitchen gear went into one wooden container, the sluice room gear in one, and the office papers, labels and documents all together in another. The orderlies would travel with their ward equipment and we would all unpack at our new destination. Lastly the Pioneers would dismantle the tents and canvas flooring. It was all very efficiently managed, although pretty hard work.

August 3rd.

We still had three patients left, but it was our last day on the ward and all we had to do was the very final packing.

I had the whole afternoon free and went for a long walk. We went past a really devastated area which reminded me of pictures of the First World War; it was a sort of bowl in a hillside which had been unmercifully bombed. The trees had been stripped bare to naked skeletons and the ground churned and grassless. There was a small graveyard there, just wooden crosses with names and pay books and several “Star of David” emblems. We went up a long hill and reached an old Norman farm building, the stone stables and cattle sheds surrounding a large cobbled yard which you entered through an archway gate, with cattle prize ribbons pinned to the walls. There were some British troops billeted there, I bought myself a mug of milk, but it was poor quality. I remember there were rabbit hutches round the yard too.

We came back to camp over the hill another way and passed a smashed light plane lying in light woodlands with ammunition spilled round it everywhere. Below on the road was an overturned truck.

August 4th.

Breakfast at 8am, but as there was nothing at all to do we could have stayed in bed longer. However, Miss Pike (Head Matron) was due to arrive, so we had to turn out in ties and berets as well as our usual battledress etc. She never turned up which we all considered very bad manners, but she probably had other commitments, or authority had slipped up over information.

A Staff Car appeared while we were waiting about, much to my astonishment, I was sent for, to the Mess tent. There was a visitor there who turned out to be Lt-Col Lidwell (Arthur St.George's C.O.). A very nice man. I can only assume that he heard via my aunt that I was in the area; it is amazing how these connections are made. He saw our C.O. and arranged for his Staff Car to pick me up the following day and to take me to see my cousin's grave. Several visitors of one kind or another then turned up all afternoon. News must have got about that we were pushing on.

The driver with the Staff Car arrived at 7.30am next morning, but for some reason, I cannot remember, we could not leave until 9am. There is a lot of waiting about in the Army! Hazel came with me. We drove through a village like something from the 1914-18 War, smashed to rubble. Burnt out tanks and lorries in the ditches, warning notices displayed by the road “Don't raise dust”, as there had been heavy shelling of transport there. Eventually we reached a small farm with an orchard at the back. By the hedge-side were three graves in a row along a ditch (just earth thrown in a mound on top). Small Army crosses with a name, number and rank. I picked a fern for his Mother (which I eventually sent her) and fixed a sprig of pressed Kilrush shamrock behind the cross, with a penciled note saying it was from his home and that his cousin had put it there.

We came back via No.3 C.C.S. (Casualty Clearing Station) and 79 General Hospital. We looked in to see one of our former members (Mrs. G) who is flying home after having had a miscarriage. This hospital was part huts and part tented and was treated as a Base. One of the ENSA women entertainers was there having psychiatric treatment.

August 6th.

A Sunday church service today for those who wished to attend. I stayed in bed. It sounded rather a feeble attempt and everyone was having arguments afterwards.

In the afternoon we had a cricket match, Sisters versus Others. The men had to bat left-handed. I don't remember the outcome, but it was good fun.

Thinking of Mrs. G, who had been our very excellent Theatre Sister, makes me realize how lucky we were to have such splendid Theatre Staff, quite apart from our Surgeons. Both the Sisters and Orderlies must have carried a very heavy work load. I remember Massey (not her real name) so often being late for meals, but always good tempered and friendly. How did she keep sane, always seeing dreadful injuries, never seeing the result of their work, though they did sometimes inquire how a certain case was faring? They certainly had my highest respect.

August 11th.

Still nothing to do. We went out for a long walk in the evening till a sea mist came up. Round by the new RAF camp on the hill behind us and back by.